The Lewis concept of acids and bases can be summaized as follows:

An acid is a substance that accepts a pair of electrons which it shares with a base, thus forming a covalent bond with the base.

A base is a substance that donates an unshared ("lone") pair of electrons to an acid, thus creating a covalent bond between the acid and base.

Proton-transfer reactions always involve electron-pair transfer

Just as any Arrhenius acid is also a Brønsted acid, any Brønsted acid is also a Lewis acid, so the various acid-base concepts are all "upward compatible". Although we don't really need to think about electron-pair transfers when we deal with ordinary aqueous-solution acid-base reactions, it is important to understand that it is the opportunity for electron-pair sharing that enables proton transfer to take place.

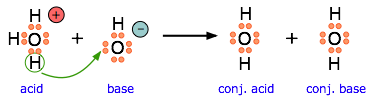

This equation for a simple acid-base neutralization shows how the Brønsted and Lewis definitions are really just different views of the same process. Take special note of the following:

- The arrow shows the movement of a proton from the hydronium ion to the hydroxide ion.

- Note carefully that the electron-pairs themselves do not move; they remain attached to their central atoms. The electron pair on the base is "donated" to the acceptor (the proton) only in the sense that it ends up being shared with the acceptor, rather than being the exclusive property of the oxygen atom in the hydroxide ion.

- Although the hydronium ion is the nominal Lewis acid here, it does not itself accept an electron pair, but acts merely as the source of the proton that coordinates with the Lewis base.

The point about the electron-pair remaining on the donor species is especially important to bear in mind. For one thing, it distinguishes a Lewis acid-base reaction from an oxidation-reduction reaction, in which a physical transfer of one or more electrons from donor to acceptor does occur.

The product of a Lewis acid-base reaction is known formally as an "adduct" or "complex", although we don't ordinarily use these terms for simple proton-transfer reactions such as the one in the above example. Here, the proton combines with the hydroxide ion to form the "adduct" H2O.

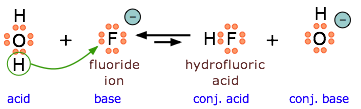

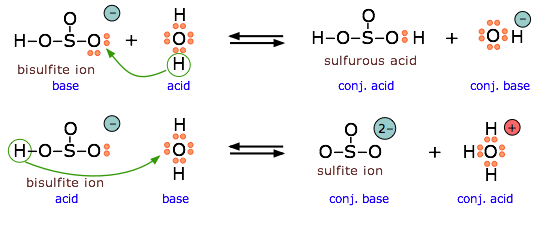

The following examples illustrate these points for some other proton-transfer reactions that you should already be familiar with.

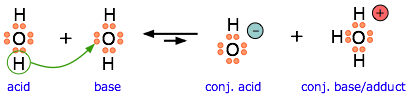

| Another example, showing the autoprotolysis of water. Note that the conjugate base is also the adduct. |  |

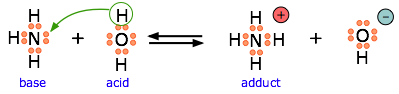

| Ammonia is both a Brønsted and a Lewis base, owing to the unshared electron pair on the nitrogen. The reverse of this reaction represents the hydrolysis of the ammonium ion. |  |

| Because HF is a weak acid, fluoride salts behave as bases in aqueous solution. As a Lewis base, F– accepts a proton from water, which is transformed into a hydroxide ion. |  |

| The bisulfite ion, being amphiprotic, can act as an electron donor or acceptor. |  |

The major utility of the Lewis definition is that it extends the concept of acids and bases beyond the realm of proton transfer reactions.

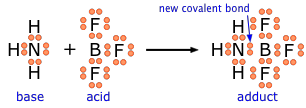

The classic example, given in every textbook, is the reaction of boron trifluoride with ammonia to form an adduct:

BF3 + NH3 → F3B-NH3

If you are already familiar with the concept of hybrid orbitals, this diagram (from a Purdue University site which is well worth looking at) might help you visualize this process. The lone pair electrons on the nitrogen atom can be acommodated in the empty 2pz orbital of BF3, creating a shared-electron B–N bond.

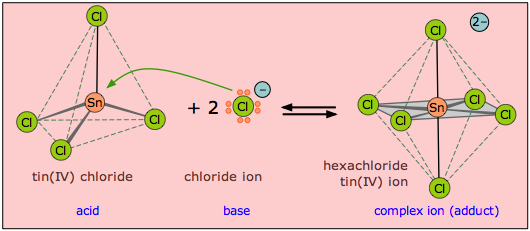

One of the most commonly-encountered kinds of Lewis acid-base reactions occurs when electron-donating ligands form coordination complexes with transition-metal ions.

In this example, the tin atom in SnCl4 can expand its valence shell by utilizing a pair of d-orbitals, changing its hybridization from sp3 to sp3d2.

Here are several more examples of Lewis acid-base reactions that cannot be accommodated within the Brønsted or Arrhenius models; be sure you are able to identify the Lewis acid and Lewis base in each reaction.

Al(OH)3 + OH– → Al(OH)4–

SnS2 + S2–→ SnS32–

Cd(CN)2 + 2 CN–→ Cd(CN)42+

AgCl + 2 NH3→ Ag(NH3)2+ + Cl–

Fe2+ + NO → Fe(NO)2+

Ni2+ + 6 NH3→ Ni(NH3)52+

Lewis acids and bases in organic reaction mechanisms

Although organic chemistry is beyond the scope of these lessons, it is instructive to see how electron donors and acceptors play a role in chemical reactions. The following two diagrams (from this site by William Reusch of Michigan State U.) show the mechanisms of two common types of reactions initiated by simple inorganic Lewis acids:

In each case, the species labeled "Complex" is an intermediate that decomposes into the products, which are conjugates of the original acid and base pairs. The electric charges indicated in the complexes are formal charges, but those in the products are "real".

In (1), the incomplete octet of the aluminum atom in AlCl3 serves as a better electron acceptor to the chlorine atom than does the isobutyl part of the base. In (2), the pair of non-bonding electrons on the dimethyl ether coordinates with the electron-deficient boron atom, leading to a complex that breaks down by releasing a bromide ion.

Note: Lewis acids are often referred to as electrophiles ("electron lovers"), reflecting the fact that they seek out electron pairs to share with bases. Similarly, bases, which have electron pairs available to share with acids, are called nucleophiles ("nucleus-lovers", referring to their being attracted to more positive centers; recall that positive charge always originates in the atomic nucleus.) This nomenclature is widely used in modern organic chemistry.

We ordinarily think of Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reactions as taking place in aqueous solutions, but this need not always be the case. A more general view encompasses a variety of acid-base solvent systems, of which the water system is only one. Each of these has as its basis an amphiprotic solvent (one capable of undergoing autoprotolysis), in parallel with the familiar case of water.

The ammonia system

This is the one you are most likely to encounter if you do advanced work in Chemistry. Liquid ammonia boils at –33° C, and can conveniently be maintained as a liquid by cooling with dry ice (–77° C.) It is a good solvent for substances that also dissolve in water, such as ionic salts and organic compounds capable of forming hydrogen bonds.

Ammonia-based life - an interesting article

Many other familiar substances can serve as the basis of protonic solvent systems, a few of which are listed here:

solvent |

autoprotolysis reaction |

pKap |

| water | 2 H2O → H3O+ + OH– | 14 |

| ammonia | 2 NH3 → NH4+ + NH2– | 33 |

| acetic acid | 2 CH3COOH → CH3COOH2+ + CH3COO– | 13 |

| ethanol | 2 C2H5OH → C2H5OH2+ + C2H5O– | 19 |

| hydrogen peroxide | 2 HO-OH → HO-OH2+ + HO-O– | 13 |

| hydrofluoric acid | 2 HF → H2F+ + F– | 10 |

| sulfuric acid | 2 H2SO4 → H3SO4+ + HSO4– | 3.5 |

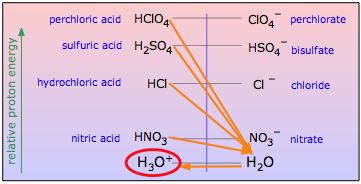

Un-leveling the strong acids

One use of nonaqueous acid-base systems is to examine the relative strengths of the strong acids and bases, whose strengths are "leveled" by the fact that they are all totally converted into H3O+ or OH– ions in water. By studying them in appropriate non-aqueous solvents which are poorer acceptors or donors of protons, their relative strengths can be determined.

One use of nonaqueous acid-base systems is to examine the relative strengths of the strong acids and bases, whose strengths are "leveled" by the fact that they are all totally converted into H3O+ or OH– ions in water. By studying them in appropriate non-aqueous solvents which are poorer acceptors or donors of protons, their relative strengths can be determined.