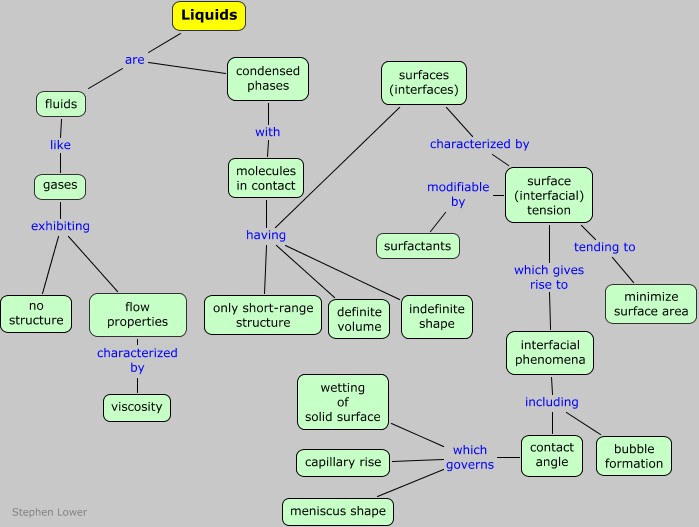

Liquids and their interfaces

Viscosity, surface tension, wetting, bubbles

Note: this document will print in an appropriately modified format (15 pages)

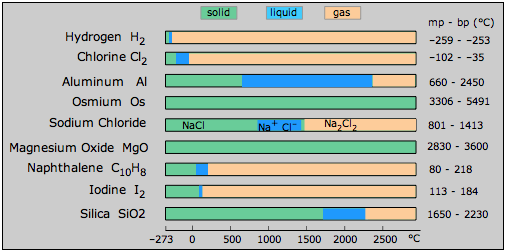

Liquids occupy a rather peculiar place in the trinity of solid, liquid and gas. A liquid is the preferred state of a substance at temperatures intermediate between the realms of the solid and the gas. But if you look at the melting and boiling points of a variety of substances , you will notice that the temperature range within which many liquids can exist tends to be rather small. In this, and in a number of other ways, the liquid state appears to be somewhat tenuous and insecure, as if it had no clear right to exist at all, and only does so as an oversight of Nature.

Certainly the liquid state is the most complicated of the three states of matter to analyze and to understand. But just as people whose personalities are more complicated and enigmatic are often the most interesting ones to know, it is these same features that make the liquid state of matter the most fascinating to study.

How do we know it’s a liquid?

Anyone can usually tell if a substance is a liquid simply by looking at it. What special physical properties do liquids possess that make them so easy to recognize? One obvious property is their mobility, which refers to their ability to move around, to change their shape to conform to that of a container, to flow in response to a pressure gradient, and to be displaced by other objects. But these properties are shared by gases, the other member of the two fluid states of matter. The real giveaway is that a liquid occupies a fixed volume, with the consequence that a liquid possesses a definite surface. Gases, of course, do not; the volume and shape of a gas are simply those of the container in which it is confined. The higher density of a liquid also plays a role here; it is only because of the large density difference between a liquid and the space above it that we can see the surface at all. (What we are really seeing are the effects of reflection and refraction that occur when light passes across the boundary between two phases differing in density, or more precisely, in their refractive indexes.)

Flow properties of liquids: the viscosity

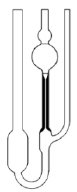

The term viscosity is a measure of resistance to flow. It can be measured by observing the time required for a given volume of liquid to flow through the narrow part of a viscometer tube.

The term viscosity is a measure of resistance to flow. It can be measured by observing the time required for a given volume of liquid to flow through the narrow part of a viscometer tube.

The viscosity of a substance is related to the strength of the forces acting between its molecular units. In the case of water, these forces are primarily due to hydrogen bonding. Liquids such as syrups and honey are much more viscous because the sugars they contain are studded with hydroxyl groups (–OH) which can form multiple hydrogen bonds with water and with each other, producing a sticky disordered network.

| water HOH | 1.00 |

| diethyl ether (CH3-CH2)2O |

0.23 |

| benzene C6H6 | 0.65 |

| glycerin C3H2(OH)3 | 280 |

| mercury | 1.5 |

| motor oil, SAE30 | 200 |

| honey | ~10,000 |

| molasses | ~5000 |

| pancake syrup | ~3000 |

Even in the absence of hydrogen bonding, dispersion forces are universally present. In smaller molecules such as ether and benzene, and also in metallic mercury, these forces are so weak that these liquids have very small viscosities. But because these forces are additive, they can be very significant in long carbon-chain molecules such as those found in oils used in cooking and for lubrication. These long molecules also tend to become entangled with one another, further increasing their resistance to flow.

Why viscosity changes with temperature

The temperature dependence of the viscosity of liquids is well known to anyone who has tried to pour cold syrup on a pancake. Because the forces that give rise to viscosity are weak, they are easily overcome by thermal motions, so it is no surprise that viscosity decreases as the temperature rises.

| T/°C | 0 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| viscosity/cP | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

For more on viscosity, see this Physics Hypertextbok page.

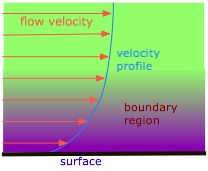

How viscosity impedes flow

The pressure drop that is observed when a liquid flows through a pipe is a direct consequence of viscosity. Those molecules that happen to find themselves near the inner walls of a tube tend to spend much of their time attached to the walls by intermolecular forces, and thus move forward very slowly.

How surface tension works

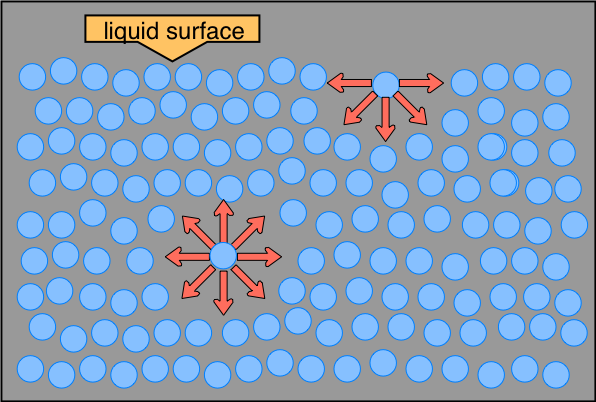

A molecule within the bulk of a liquid experiences attractions to neighboring molecules in all directions, but since these average out to zero, there is no net force on the molecule because it is, on the average, as energetically comfortable in one location within the liquid as in another.

Liquids ordinarily do have surfaces, however, and a molecule that finds itself in such a location is attracted to its neighbors below and to either side, but there is no attraction operating in the 180° solid angle above the surface. As a consequence, a molecule at the surface will tend to be drawn into the bulk of the liquid. Conversely, work must be done in order to move a molecule within a liquid to its surface.

Why liquids form drops

Clearly there must always be some molecules at the surface, but the smaller the surface area, the lower the potential energy. Thus intermolecular attractive forces act to minimize the surface area of a liquid.

The geometric shape that has the smallest ratio of surface area to volume is the sphere, so very small quantities of liquids tend to form spherical drops. As the drops get bigger, their weight deforms them into the typical tear shape.

The geometric shape that has the smallest ratio of surface area to volume is the sphere, so very small quantities of liquids tend to form spherical drops. As the drops get bigger, their weight deforms them into the typical tear shape.

... and bubbles

Think of a bubble as a hollow drop. Surface tension acts to minimize the surface, and thus the radius of the spherical shell of liquid, but this is opposed by the pressure of vapor trapped within the bubble. For a more detailed analysis, see here. We discuss bubbles in much more detail farther down on this page.

The surface film

The imbalance of forces near the upper surface of a liquid has the effect of an elastic film stretched across the surface. You have probably seen water striders and other insects take advantage of this when they walk across a pond. Similarly, you can carefully "float" a light object such as a steel paperclip on the surface of water in a cup. (How to do it)

The imbalance of forces near the upper surface of a liquid has the effect of an elastic film stretched across the surface. You have probably seen water striders and other insects take advantage of this when they walk across a pond. Similarly, you can carefully "float" a light object such as a steel paperclip on the surface of water in a cup. (How to do it)

Left: Raft spider by thomsonalasdair; Right: photo by Jeffffd

Surface tensions of common liquids

| substance | surface tension |

|---|---|

| water H(OH) | 72.7 dyne/cm |

| diethyl ether (CH3-CH2)2O | 17.0 |

| 40.0 | |

| glycerin C3H2(OH)3 | 63 |

| mercury (15°C) | 487 |

| n-octane | 21.8 |

| sodium chloride solution (6M in water) | 82.5 |

| sucrose solution (85% in water) |

76.4 |

| sodium oleate (soap) solution in water | 25 |

The table shows the surface tensions of several liquids at room temperature. Note especially that

- hydrocarbons and non-polar liquids such as ether have rather low values

- one of the main functions of soaps and other surfactants is to reduce the surface tension of water

- mercury has the highest surface tension of any liquid at room temperature. It is so high that mercury does not flow in the ordinary way, but breaks into small droplets that roll independently.

Surface tension and viscosity are not directly related, as you can verify by noting the disparate values of these two quantities for mercury. Viscosity depends on intermolecular forces within the liquid, whereas surface tension arises from the difference in the magnitudes of these forces within the liquid and at the surface.

Surface tension changes with temperature

| °C | dynes/cm |

|---|---|

| 0 | 75.9 |

| 20 | 72.7 |

| 50 | 67.9 |

| 100 | 58.9 |

"Tears" in a wine glass: effects of a surface tension gradient

Why do "tears" form inside a wine glass? You have undoubtedly noticed this; pour some wine into a glass, and after a few minutes, droplets of clear liquid can be seen forming on the inside walls of the glass about a centimeter above the level of the wine. This happens even when the wine and the glass are at room temperature, so it has nothing to do with condensation.

Why do "tears" form inside a wine glass? You have undoubtedly noticed this; pour some wine into a glass, and after a few minutes, droplets of clear liquid can be seen forming on the inside walls of the glass about a centimeter above the level of the wine. This happens even when the wine and the glass are at room temperature, so it has nothing to do with condensation.

The explanation involves Raoult's law, hydrogen bonding, adsorption, and surface tension, so this phenomenon makes a good review of much you have learned about liquids and solutions.

The tendency of a surface tension gradient to draw water into the region of higher surface tension is known as the Maringoni effect. The image looking down into a wine glass is from an MIT study.

First, remember that both water and alcohol are hydrogen-bonding liquids; as such, they are both strongly attracted to the oxygen atoms and -OH groups on the surface of the glass. This causes the liquid film to creep up the walls of the glass. Alcohol, the more volatile of the two liquids, vaporizes more readily, causing the upper (and thinnest) part of the liquid film to become enriched in water. Because of its stronger hydrogen bonding, water has a larger surface tension than alcohol, so as the alcohol evaporates, the surface tension of the upper part of the liquid film increases. This that part of the film draw up more liquid and assume a spherical shape which gets distorted by gravity into a "tear", which eventually grows so large that gravity wins out over adsorption, and the drop falls back into the liquid, soon to be replaced by another.

First, remember that both water and alcohol are hydrogen-bonding liquids; as such, they are both strongly attracted to the oxygen atoms and -OH groups on the surface of the glass. This causes the liquid film to creep up the walls of the glass. Alcohol, the more volatile of the two liquids, vaporizes more readily, causing the upper (and thinnest) part of the liquid film to become enriched in water. Because of its stronger hydrogen bonding, water has a larger surface tension than alcohol, so as the alcohol evaporates, the surface tension of the upper part of the liquid film increases. This that part of the film draw up more liquid and assume a spherical shape which gets distorted by gravity into a "tear", which eventually grows so large that gravity wins out over adsorption, and the drop falls back into the liquid, soon to be replaced by another.

The surface tension discussed immediately above is an attribute of a liquid in contact with a gas (ordinarily the air or vapor) or a vacuum. But if you think about it, the molecules in the part of a liquid that is in contact with any other phase (liquid or solid) will experience a different balance of forces than the molecules within the bulk of the liquid. Thus surface tension is a special case of the more general interfacial tension which is defined by the work associated with moving a molecule from within the bulk liquid to the interface with any other phase.

Wetting of surfaces

Take a plastic mixing bowl from your kitchen, and splash some water around in it. You will probably observe that the water does not cover the inside surface uniformly, but remains dispersed into drops. Do the same thing with a perfectly clean glass container, and you will see that the water forms a smooth film on the glass surface; we say that the glass is wetted by the water.

Anyone who has driven a car knows that water poured onto a freshly-cleaned windshield will form a uniform film, but after driving in heavy traffic, the glass surface gets coated with greasy material; running the wipers under these conditions simply breaks hundreds of drops into thousands.

Anyone who has driven a car knows that water poured onto a freshly-cleaned windshield will form a uniform film, but after driving in heavy traffic, the glass surface gets coated with greasy material; running the wipers under these conditions simply breaks hundreds of drops into thousands.

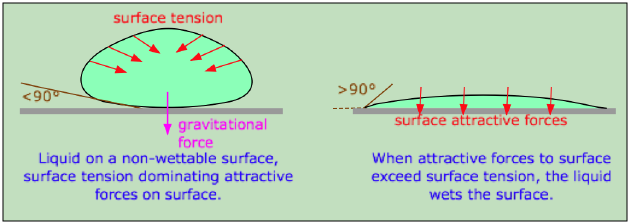

When a molecule of a liquid is in contact with another phase, its behavior depends on the relative attractive strengths of its neighbors on the two sides of the phase boundary. If the molecule is more strongly attracted to its own kind, then interfacial tension will act to minimize the area of contact by increasing the curvature of the surface. This is what happens at the interface between water and a hydrophobic surface such as a plastic mixing bowl or a windshield coated with oily material.

A liquid will wet a surface if the angle at which it makes contact with the surface is less than 90°. The value of this contact angle can be predicted from the properties of the liquid and solid separately.

A liquid will wet a surface if the angle at which it makes contact with the surface is less than 90°. The value of this contact angle can be predicted from the properties of the liquid and solid separately.

A clean glass surface, by contrast, has –OH groups (from hydrated SiO2 structures) sticking out of it which readily attach to water molecules through hydrogen bonding; the lowest potential energy now occurs when the contact area between the glass and water is maximized. This causes the water to spread out evenly over the surface, or to wet it.

You have undoubtedly noticed water droplets sitting on the hydrophobic surface of most plant leaves. It is created by a thin layer of cells that secrete a waxy substance that prevents excessive water loss; few plants would survive dry weather without this coating. Our own skin is fairly easily wetted when very clean, but is soon covered with an oily-waxy substanced secreted by the sebaceous glands; its function is to lubricate and waterproof the skin. Its effect can be readily seen when perspiration turns into beads of sweat.

You have undoubtedly noticed water droplets sitting on the hydrophobic surface of most plant leaves. It is created by a thin layer of cells that secrete a waxy substance that prevents excessive water loss; few plants would survive dry weather without this coating. Our own skin is fairly easily wetted when very clean, but is soon covered with an oily-waxy substanced secreted by the sebaceous glands; its function is to lubricate and waterproof the skin. Its effect can be readily seen when perspiration turns into beads of sweat.

Surfactants

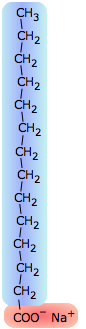

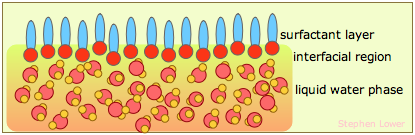

The surface tension of water can be reduced to about one-third of its normal value by adding some soap or synthetic detergent. These substances, known collectively as surfactants, are generally hydrocarbon molecules having an ionic group on one end. The ionic group, being highly polar, is strongly attracted to water molecules; we say it is hydrophilic. The hydrocarbon (hydrophobic) portion is just the opposite; inserting it into water would break up the local hydrogen-bonding forces and is therefore energetically unfavorable. What happens, then, is that the surfactant molecules migrate to the surface with their hydrophobic ends sticking out, effectively creating a new surface. Because hydrocarbons interact only through very weak dispersion forces, this new surface has a greatly reduced surface tension.

The surface tension of water can be reduced to about one-third of its normal value by adding some soap or synthetic detergent. These substances, known collectively as surfactants, are generally hydrocarbon molecules having an ionic group on one end. The ionic group, being highly polar, is strongly attracted to water molecules; we say it is hydrophilic. The hydrocarbon (hydrophobic) portion is just the opposite; inserting it into water would break up the local hydrogen-bonding forces and is therefore energetically unfavorable. What happens, then, is that the surfactant molecules migrate to the surface with their hydrophobic ends sticking out, effectively creating a new surface. Because hydrocarbons interact only through very weak dispersion forces, this new surface has a greatly reduced surface tension.

Chemistry of washing

>

>

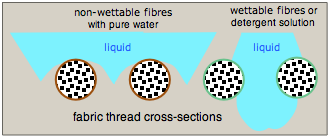

How do soaps and detergents help get things clean? There are two main mechanisms. First, by reducing water's suface tension, the water can more readily penetrate fabrics (see the illustration under "Water repellency" below.) Secondly, much of what we call "dirt" consists of non-water soluble oils and greasy materials which the hydrophobic ends of surfactant molecules can penetrate. When they do so in sufficient numbers and with their polar ends sticking out, the resulting aggregate can hydrogen-bond to water and becomes "solubilized".

How do soaps and detergents help get things clean? There are two main mechanisms. First, by reducing water's suface tension, the water can more readily penetrate fabrics (see the illustration under "Water repellency" below.) Secondly, much of what we call "dirt" consists of non-water soluble oils and greasy materials which the hydrophobic ends of surfactant molecules can penetrate. When they do so in sufficient numbers and with their polar ends sticking out, the resulting aggregate can hydrogen-bond to water and becomes "solubilized".

Washing is usually more effective in warm water; higher temperatures reduce the surface tension of the water and make it easier for the surfactant molecules to penetrate the material to be removed.

"Magnetic laundry disks" which are supposed to reduce the surface tension of water (thus eliminating the the need for detergents) are widely promoted to chemistry-challenged consumers on the Internet. See here for more on these scams.)

"Magnetic laundry disks" which are supposed to reduce the surface tension of water (thus eliminating the the need for detergents) are widely promoted to chemistry-challenged consumers on the Internet. See here for more on these scams.)Water repellency

Image of a water drop on a porous fabric treated with a non-wettable coating. [Wikimedia]

Water is quite strongly attracted to many natural fibers such as cotton and linen through hydrogen-bonding to their cellulosic hydroxyl groups. A droplet that falls on such a material will flatten out and be drawn through the fabric. One way to prevent this is to coat the fibers with a polymeric material that is not readily wetted. The water tends to curve away from the fibers so as to minimize the area of contact, so the droplets are supported on the gridwork of the fabric but tend not to fall through.

Capillary rise

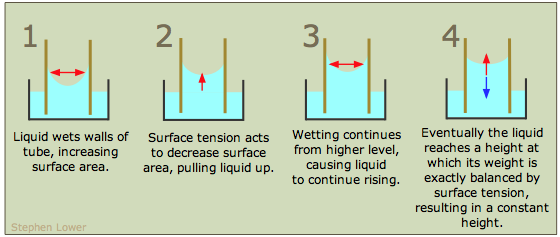

If the walls of a narrow tube can be efficiently wetted by a liquid, then the the liquid will be drawn up into the tube by capillary action. This effect is only noticeable in narrow containers (such as burettes) and especially in small-diameter capillary tubes. The smaller the diameter of the tube, the higher will be the capillary rise.

A clean glass surface is highly attractive to most molecules, so most liquids display a concave meniscus in a glass tube.

To help you understand capillary rise, the above diagram shows a glass tube of small cross-section inserted into an open container of water. The attraction of the water to the inner wall of the tube pulls the edges of the water up, creating a curved meniscus whose surface area is smaller than the cross-section area of the tube. The surface tension of the water acts against this enlargement of its surface by attempting to reduce the curvature, stretching the surface into a flatter shape by pulling the liquid farther up into the tube. This process continues until the weight of the liquid column becomes equal to the surface tension force, and the system reaches mechanical equilibrium.

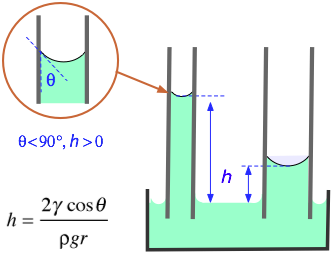

Capillary rise results from a combination of two effects: the tendency of the liquid to wet (bind to) the surface of the tube (measured by the value of the contact angle), and the action of the liquid's surface tension to minimize its surface area.

In the formula shown at the left (which you need not memorize!)

h = elevation of the liquid (m)

γ = surface tension (N/m)

θ = contact angle (radians)

ρ = density of liquid (kg/m3)

g = acceleration of gravity (m/s–2)

r = radius of tube (m)

See this Wikipedia article for the derivation.

The contact angle between water and ordinary soda-lime glass is essentially zero; since the cosine of 0 radians is unity, its capillary rise is especially noticable. In general, water can be drawn very effectively into narrow openings such as the channels between fibers in a fabric and into porous materials such as soils.

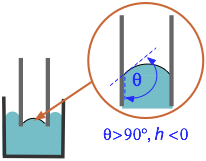

Note that if θ is greater than 90° (π/2 radians), the capillary "rise" will be negative — meaning that the molecules of the liquid are more strongly attracted to each other than to the surface. This is readily seen with mercury in a glass container, in which the meniscus is upwardly convex instead of concave.

Note that if θ is greater than 90° (π/2 radians), the capillary "rise" will be negative — meaning that the molecules of the liquid are more strongly attracted to each other than to the surface. This is readily seen with mercury in a glass container, in which the meniscus is upwardly convex instead of concave.

The Meniscus Madness page is a good source

of photos and activities aimed at middle school.

Capillary action and trees

Capillary rise is the principal mechanism by which water is able to reach the highest parts of trees. Water strongly bonds to the narrow (25 μM) cellulose channels in the xylem. (Osmotic pressure and "suction" produced by loss of water vapor through the leaves also contribute to this effect, and are the main drivers of water flow in smaller plants.) For an interesting discussion of these effects, see this site.

Bubbles

Bubbles can be thought of as "negative drops" — spherical spaces within a liquid containing a gas, often just the vapor of the liquid. Bubbles within pure liquids such as water (which we see when water boils) are inherently unstable because the liquid's surface tension causes them to collapse. But in the presence of a surfactant, bubbles can be stabilized and given an independent if evanescent existence.

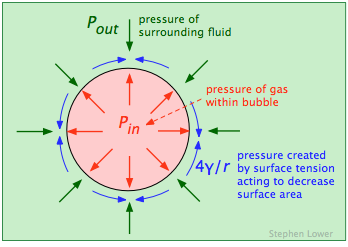

The pressure of the gas inside a bubble Pin must be sufficient to oppose the pressure outside of it (Pout, the atmospheric pressure plus the hydrostatic pressure of any other fluid in which the bubble is immersed. But the force caused by surface tension γ of the liquid boundary also tends to collapse the bubble, so Pin must be greater than Pout by the amount of this force, which is given by 4γ/r:

The pressure of the gas inside a bubble Pin must be sufficient to oppose the pressure outside of it (Pout, the atmospheric pressure plus the hydrostatic pressure of any other fluid in which the bubble is immersed. But the force caused by surface tension γ of the liquid boundary also tends to collapse the bubble, so Pin must be greater than Pout by the amount of this force, which is given by 4γ/r:

See here for a derivation of the LaPlace equation. This page explains more about LaPlace's law and relates it to the behavior of balloons.

The most important feature of this relationship (known as LaPlace's law) is that the pressure required to maintain the bubble is inversely proportional to its radius. This means that the smallest bubbles have the greatest internal gas pressures! This might seem counterintuitive, but if you are an experienced soap-bubble blower, or have blown up a rubber balloon (in which the elastic of the rubber has an effect similar to the surface tension in a liquid), you will have noticed that you need to puff harder to begin the expansion.

Soap bubbles

All of us at one time or another have enjoyed the fascination of creating soap bubbles and admiring their intense and varied colors as they drift around in the air, seemingly aloof from the constraints that govern the behavior of ordinary objects — but only for a while! Their life eventually comes to an abrupt end as they fall to the ground or pop in mid-flight. (But in this fascinating commentary on the subject, the author cites the case of one that lasted just one day short of a year!)

image: Soap Bubbles (2007) by Shefali Nyan

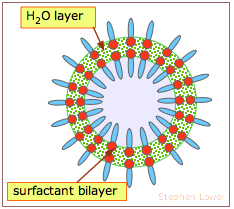

The walls of these bubbles consist of a thin layer of water molecules sandwiched between two layers of surfactant molecules. Their spherical shape is of course the result of water's surface tension. Although the surfactant (soap) initially reduces the surface tension, expansion of the bubble spreads the water into a thiner layer and spreads the surfactant molecules over a wider area, deceasing their concentration. This, in turn, allows the water molecules to interact more strongly, increasing its surface tension and stabilizing the bubble as it expands.

The bright colors we see in bubbles arise from interference between light waves that are reflected back from the inner and outer surfaces, indicating that the thickness of the water layer is comparable the range of visible light (around 400-600 nm).

Once the bubble is released, it can endure until it strikes a solid surface or collapses owing to loss of the water layer by evaporation. The latter process can be slowed by adding a bit of glycerine to the liquid. A variety of recipes and commercial "bubble-making solutions" are available; some of the latter employ special liquid polymers which slow evaporation and greatly extend the bubble lifetimes. Bubbles blown at very low temperatures can be frozen, but these eventually collapse as the gas diffuses out.

Bubbles, surface tension, and breathing

The sites of gas exchange with the blood in mammalian lungs are tiny sacs known as alveoli. In humans there are about 150 million of these, having a total surface area about the size of a tennis court.

The inner surface of each alveolus is about 0.25 mm in diameter and is coated with a film of water, whose high surface tension not only resists inflation, but would ordinarily cause the thin-walled alveoli to collapse. In order to counteract this effect, special cells in the alveolar wall secrete a phospholipid pulmonary surfactant that reduces the surface tension of the water film to about 35% of its normal value. But there is another problem: the alveoli can be regarded physically as a huge collection of interconnected bubbles of varying sizes. As noted above, the surface tension of a surfactant-stabilized bubble increases with their size. So by making it easier for the smaller alveoli to expand while inhibiting the expansion of the larger ones, the surfactant helps to equalize the volume changes of all the alveoli as one inhales and exhales.

Pulmonary surfactant is produced only in the later stages of fetal development, so premature infants often don't have enough and are subject to respiratory distress syndrome which can be fatal.

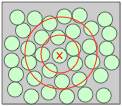

You can think of a simple liquid such as argon or methane as a collection of loosely-packed marbles that can assume various shapes. Although the overall arrangement of the individual molecular units is entirely random, there is a certain amount of short-range order: the presence of one molecule at a given spot means that the neighboring molecules must be at least as far away as the sum of the two radii, and this in turn affects the possible locations of more distant concentric shells of molecules.

Although the overall arrangement of the individual molecular units is entirely random, there is a certain amount of short-range order: the presence of one molecule at a given spot means that the neighboring molecules must be at least as far away as the sum of the two radii, and this in turn affects the possible locations of more distant concentric shells of molecules.

An important consequence of the disordered arrangement of molecules in a liquid is the presence of void spaces. These, together with the increased kinetic energy of colliding molecules which helps push them apart, are responsible for the approximately 15-percent decrease in density that is observed when solids based on simple spherical molecules such as Ne and Hg melt into liquids. These void spaces are believed to be the key to the flow properties of liquids; the more “holes” there are in the liquid, the more easily the molecules can slip and slide over one another.

As the temperature rises, thermal motions of the molecules increase and the local structure begins to deteriorate, as shown in the plots below.

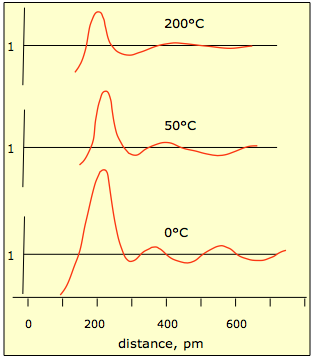

There is very little experimental information on the structure of liquids, other than the X-ray diffraction studies that yield plots such as this one for liquid mercury.

This plot shows the relative probability of finding a mercury atom at a given distance from another atom located at distance 0. You can see that as thermal motions increase, the probabilities even out at greater distances.

It is very difficult to design experiments that yield the kind of information required to define the microscopic arrangement of molecules in the liquid state.

Many of our current ideas on the subject come from computer simulations based on hypothetical models. In a typical experiment, the paths of about 1000 molecules in a volume of space are calculated. The molecules are initially given random kinetic energies whose distribution is consistent with the Boltzmann distribution for a given temperature. The trajectories of all the molecules are followed as they change with time due to collisions and other interactions; these interactions must be calculated according to an assumed potential energy-vs.-distance function that is part of the particular model being investigated.

These computer experiments suggest that whatever structure simple liquids do possess is determined mainly by the repulsive forces between the molecules; the attractive forces act in a rather nondirectional, general way to hold the liquid together. It is also found that if spherical molecules are packed together as closely as geometry allows (in which each molecule would be in contact with twelve nearest neighbors), the collection will have a long-range order characteristic of a solid until the density is decreased by about ten percent, at which point the molecules can slide around and move past one another, thus preserving only short-range order. In recent years, experimental studies based on ultra-short laser flashes have revealed that local structures in liquids have extremely short lifetimes, of the order of picoseconds to nanoseconds.

It has long been suspected that the region of a liquid that bounds a solid surface is more ordered than within the bulk liquid. This has been confirmed for the case of water in contact with silicon, in which the liquid structure close to the surface is similar to what is found in liquid crystals.

It has long been suspected that the region of a liquid that bounds a solid surface is more ordered than within the bulk liquid. This has been confirmed for the case of water in contact with silicon, in which the liquid structure close to the surface is similar to what is found in liquid crystals.

(The illustration is from a 1999 article in Physical Review Focus.)