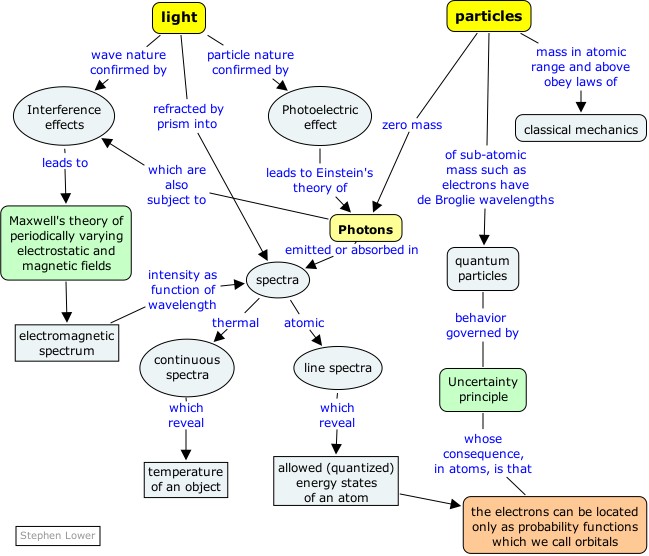

Atoms are far too small to see directly, even with the most powerful optical microscopes. But atoms do interact with light, and under some circumstances emit light in ways that reveal their internal structures in amazingly fine detail. It is through the "language of light" that we communicate with the world of the atom. This section will introduce you to the rudiments of this language.

[New Zealand Institute of Physics]

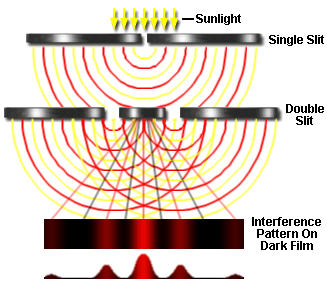

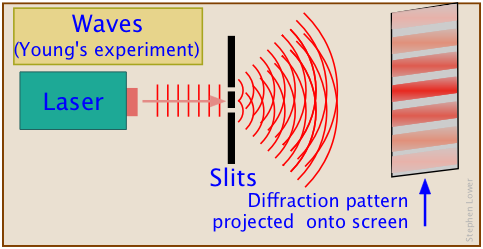

Young's experiment deconstructed

Nothing new here (not since 1799, anyway!) This works for all kinds of physical waves — light, ocean, sound...

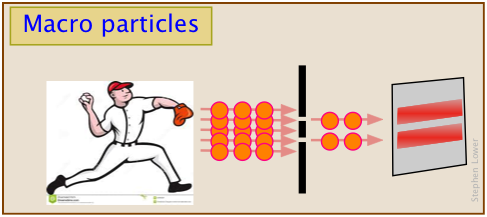

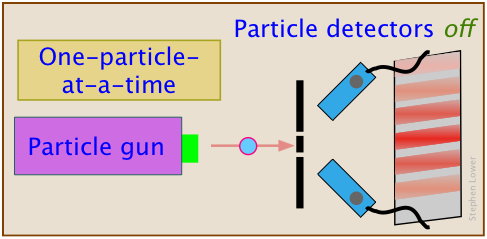

Shrink our baseballs down to atomic size, and shoot our particles one-at-a-time at the pair of slits, and the pattern that builds up is similar to the kind that Mr. Young observed.

This works for photons (light), electrons, atoms, and small molecules.

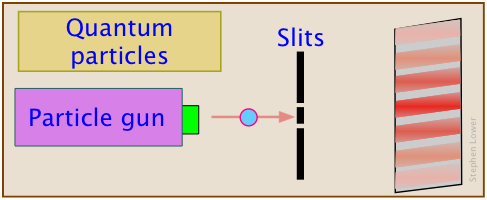

Quantum weirdness emerges

OK, this suggests that particles have wave-like properties. But something very strange is going on here:

First, consider how the above experiment differs from Young's. His light source was a continuous beam of huge numbers of photons that can only be treated as a "wave". The process we are describing here is carried out experimentally not with a "photon gun", but by simply reducing the intensity of the light to such an unimaginably small level that only one photon is in transit at a time. So even if we admit that the photon "has wave-like properties", we know that it takes two waves (and thus presumably two photons) to form an interference pattern.

This raises the question: how can a single photon/"wave" (or whatever we wish to call it) emerge from the double-slit system as two wave-like entities that combine to form typical wave-derived interference pattern?

There is no clear answer to this question. Perhaps the simplest explanation is that the photon passes through both slits. Welcome to the world of quantum weirdness!

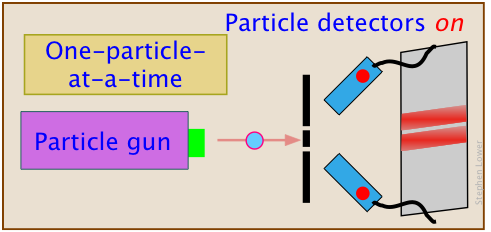

It gets even weirder

One way of resolving this question might be to aim two "particle detectors" at each  slit, in the hope that we can determine what emerges from each one.

slit, in the hope that we can determine what emerges from each one.

This kind of experiment has actually been done, both with photons and electrons.

The result is even more weird: the quantum-nature of the particles disappears.

They act as if they were baseballs!

Now, repeat the last experiment, making only one change: turn the particle detectors off.

Voilà — pulling the plug on the particle detectors restores the quantum nature of the particles.

So apparently, the particle somehow "knows" that it is being watched, and reveals its wave-like nature again.

Now this is really weird!

There is a good Wikipedia article that explains this in more detail. See also the article on the many-worlds interpretation of these phenomena.

The apparent"intelligence" of quantum particles

One well-known physicist (Landé) suggested that perhaps we should coin a new word, wavicle, to reflect this duality.

For large bodies (most atoms, baseballs, cars) there is no question: the wave properties are insignificant, and the laws of classical mechanics can adequately describe their behaviors. But for particles as tiny as electrons (quantum particles), the situation is quite different: instead of moving along well defined paths, a quantum particle seems to have an infinity of paths which thread their way through space, seeking out and collecting information about all possible routes, and then adjusting its behavior so that its final trajectory, when combined with that of others, produces the same overall effect that we would see from a train of waves of wavelength = h/mv.

If cars behaved as quantum particles,

Image source: Loyola U - "The double-slit garage experiment" from Annals of Improbable Research.

|

|

Will Schrödinger's cat come back?

See this Wikipedia article for a nice discussion of Schrödinger's cat paradox.

Taking this idea of quantum indeterminacy to its most extreme, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger proposed a "thought experiment" in which the radioactive decay of an atom would initiate a chain of events that would lead to the death of a cat placed in a closed box. The atom has a 50% chance of decaying in an hour, meaning that its wave representation will contain both possibilities until an observation is made.

Taking this idea of quantum indeterminacy to its most extreme, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger proposed a "thought experiment" in which the radioactive decay of an atom would initiate a chain of events that would lead to the death of a cat placed in a closed box. The atom has a 50% chance of decaying in an hour, meaning that its wave representation will contain both possibilities until an observation is made.

Suppose that the decay of this atom will initiate a process in which a hammer drops onto, and breaks, a vial of liquid having a poisonous vapor.

Suppose that the decay of this atom will initiate a process in which a hammer drops onto, and breaks, a vial of liquid having a poisonous vapor.

The question, then, is will the cat be simultaneously in an alive-and-dead state until the box is opened? If so, this raises all kinds of interesting questions about the nature of reality.

[image]

The saga of Schrödinger's cat has inspired a huge amount of commentary and speculation, as well as books, poetry, songs, T-shirts, etc. This Wikipedia page is devoted entirely to "Schrödinger's cat in popular culture".

If your head is still spinning from the quantum weirdness described in the preceding section, you can now relax a bit: in this section, we are back to good old classical physics!

What you need to know about waves

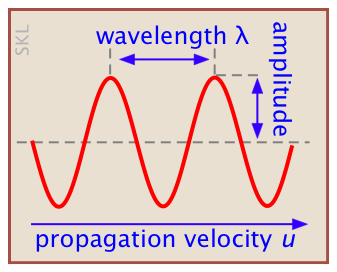

We use the term "wave" to refer to a quantity which changes with time. Waves in which the changes occur in a repeating or periodic manner are of special importance and are widespread in nature; think of the motions of the ocean surface, the pressure variations in an organ pipe, or the vibrations of a plucked guitar string. What is interesting about all such repeating phenomena is that they can be described by the same mathematical equations.

A rather nice animation of linear and transverse wave motions

Wave motion arises when a periodic disturbance of some kind is propagated through a medium; pressure variations through air, transverse motions along a guitar string, or variations in the intensities of the local electric and magnetic fields in space, which constitutes electromagnetic radiation. For each medium, there is a characteristic velocity at which the disturbance travels.

v = ν λ

Problem Example 1

What is the wavelength of the musical note A = 440 hz when it is propagated through air in which the velocity of sound is 343 m s–1?

Solution:

λ = v / ν = (343 m s–1)/(440 s–1) = 0.80 m

The nature of electromagnetic waves

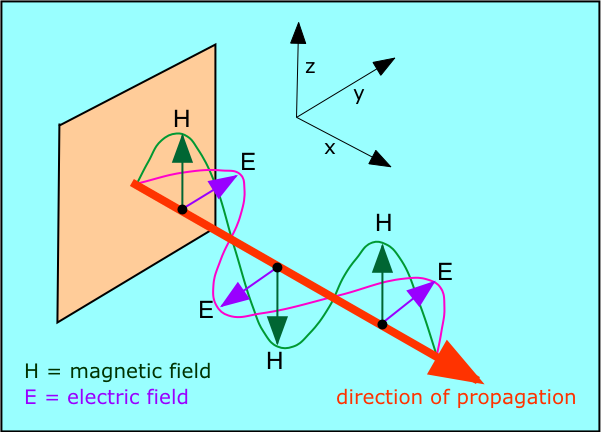

Michael Faraday's discovery that electric currents could give rise to magnetic fields and vice versa raised the question of how these effects are transmitted through space. Around 1870, the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) showed that this electromagnetic radiation can be described as a train of perpendicular oscillating electric and magnetic fields.

|

What is "waving" in electromagnetic radiation? According to Maxwell, it is the strengths of the electric and magnetic fields as they travel through space. The two fields are oriented at right angles to each other and to the direction of travel. As the electric field changes, it induces a magnetic field, which then induces a new electric field, etc., allowing the wave to propagate itself through space. |

Maxwell was able to calculate the speed at which electromagnetic disturbances are propagated, and found that this speed is the same as that of light. He therefore proposed that light is itself a form of electromagnetic radiation whose wavelength range forms only a very small part of the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Maxwell's work served to unify what were once thought to be entirely separate realms of wave motion.

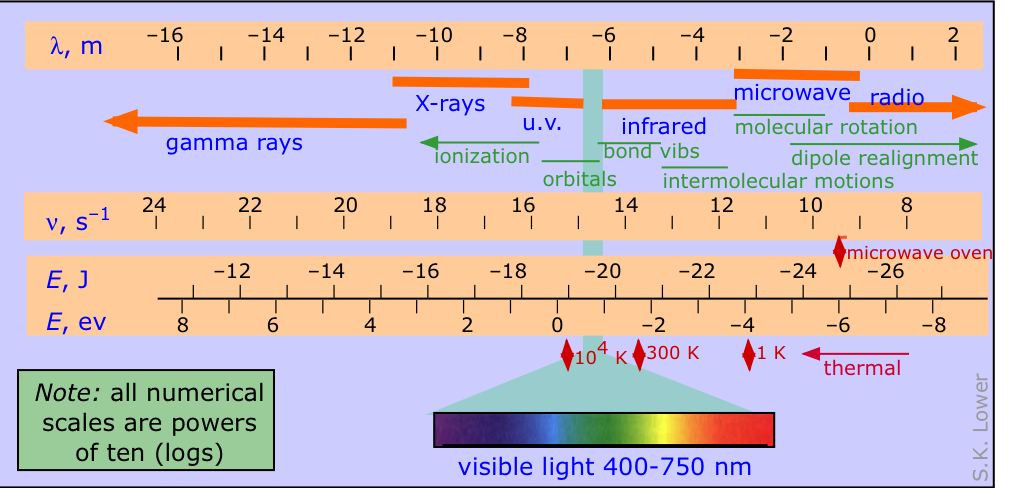

The electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is conventionally divided into various parts as depicted in the diagram below, in which the four logarithmic scales correlate the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation with its frequency in hertz (units of s–1) and the energy per photon, expressed both in joules and electron-volts.

See here for a more detailed look at the electromagnetic spectrum

Electromagnetic radiation and chemistry

It's worth noting that radiation in the ultraviolet range can have direct chemical effects by ionizing atoms and disrupting chemical bonds. Longer-wavelength radiation can interact with atoms and molecules in ways that provide a valuable means of indentifying them and revealing particular structural features.

Energy units and magnitudes

It is useful to develop some feeling for the various magnitudes of energy that we must deal with. The basic SI unit of energy is the Joule; the appearance of this unit in Planck's constant h allows us to express the energy equivalent of light in joules. For example, light of wavelength 500 nm, which appears blue-green to the human eye, would have a frequency of

The quantum of energy carried by a single photon of this frequency is

![]()

Another energy unit that is commonly employed in atomic physics is the electron volt; this is the kinetic energy that an electron acquires upon being accelerated across a 1-volt potential difference. The relationship 1 eV = 1.6022E–19 J gives an energy of 2.5 eV for the photons of blue-green light.

![]() Two small flashlight batteries will produce about 2.5 volts, and thus could, in principle, give an electron about the same amount of kinetic energy that blue-green light can supply. Because the energy produced by a battery derives from a chemical reaction, this quantity of energy is representative of the magnitude of the energy changes that accompany chemical reactions.

Two small flashlight batteries will produce about 2.5 volts, and thus could, in principle, give an electron about the same amount of kinetic energy that blue-green light can supply. Because the energy produced by a battery derives from a chemical reaction, this quantity of energy is representative of the magnitude of the energy changes that accompany chemical reactions.

In more familiar terms, one mole of 500-nm photons would have an energy equivalent of Avogadro's number times 4E–19 J, or 240 kJ per mole. This is comparable to the amount of energy required to break some chemical bonds. Many substances are able to undergo chemical reactions following light-induced disruption of their internal bonding; such molecules are said to be photochemically active.

Atoms are far too small to observe directly, even with the most powerful optical microscopes. But atoms do interact with and under some circumstances emit light in ways that reveal their internal structures in amazingly fine detail. It is through the "language of light" that we communicate with the world of the atom. This section will introduce you to the rudiments of this language.

Continuous spectra

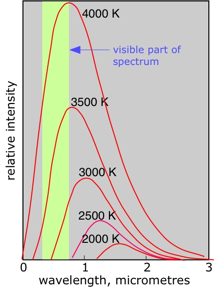

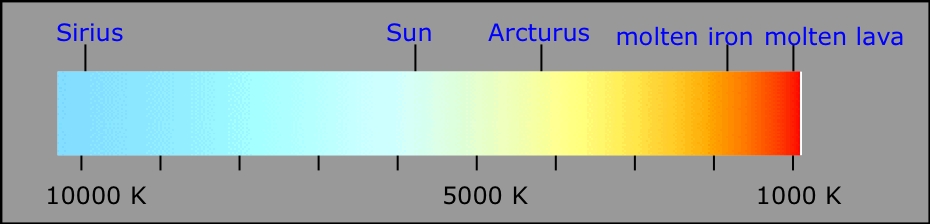

Any body whose temperature is above absolute zero emits radiation covering a broad range of wavelengths. At very low temperatures the predominant wavelengths are in the radio microwave region. As the temperature increases, the wavelengths decrease; at room temperature, most of the emission is in the infrared.

Any body whose temperature is above absolute zero emits radiation covering a broad range of wavelengths. At very low temperatures the predominant wavelengths are in the radio microwave region. As the temperature increases, the wavelengths decrease; at room temperature, most of the emission is in the infrared.

At still higher temperatures, objects begin to emit in the visible region, at first in the red, and then moving toward the blue as the temperature is raised. These thermal emission spectra are described as continuous spectra, since all wavelengths within the broad emission range are present.

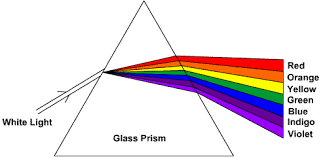

The source of thermal emission most familiar to us is the Sun. When sunlight is refracted by rain droplets into a rainbow or by a prism onto a viewing screen, we see the visible part of the spectrum.

The source of thermal emission most familiar to us is the Sun. When sunlight is refracted by rain droplets into a rainbow or by a prism onto a viewing screen, we see the visible part of the spectrum.

Wikipedia article on Solar radiation

Red hot, white hot, blue hot... your rough guide to temperatures of hot objects.

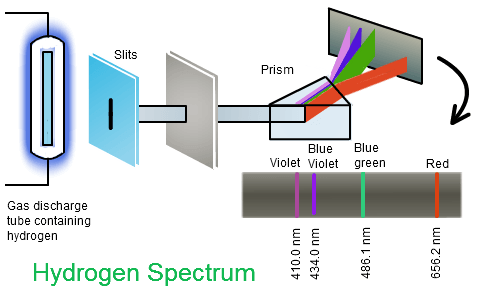

Line spectra and their uses

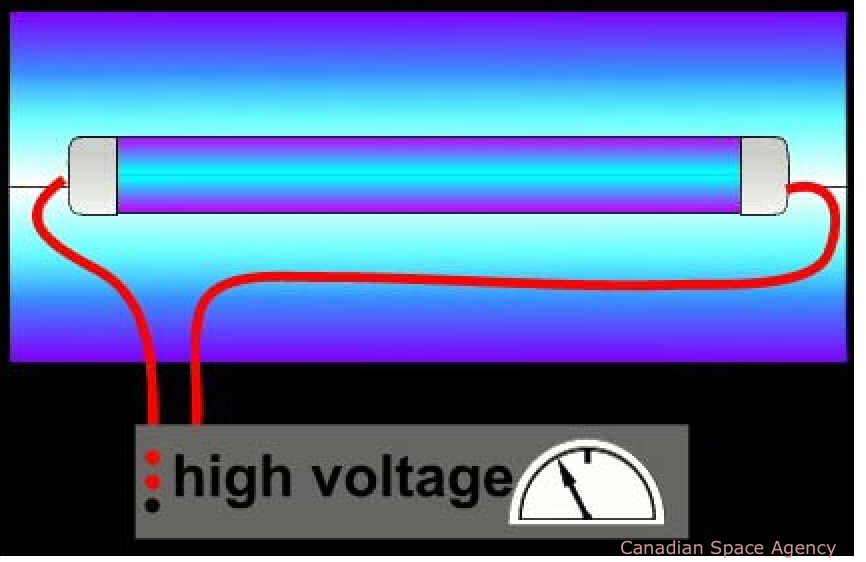

Heat a piece of iron up to near its melting point and it will emit a broad continuous spectrum that the eye perceives as orange-yellow. But if you zap the iron with an electric spark, some of the iron atoms will vaporize and have one or more of their electrons temporarily knocked out of them. As they cool down the electrons will re-combine with the iron ions, losing energy as the move in toward the nucleus and giving up this excess energy as light. The spectrum of this light is anything but continuous; it consists of a series of discrete wavelengths which we call lines.

Heat a piece of iron up to near its melting point and it will emit a broad continuous spectrum that the eye perceives as orange-yellow. But if you zap the iron with an electric spark, some of the iron atoms will vaporize and have one or more of their electrons temporarily knocked out of them. As they cool down the electrons will re-combine with the iron ions, losing energy as the move in toward the nucleus and giving up this excess energy as light. The spectrum of this light is anything but continuous; it consists of a series of discrete wavelengths which we call lines.

A spectrum is most accurately expressed as a plot of intensity as a function of wavelength. Historically, the first spectra were obtained by passing the radiation from a source through a series or narrow slits to obtain a thin beam which was dispersed by a prism so that the different wavelengths are spread out onto a photographic film or viewing screen. The "lines" in line spectra are really images of the slit nearest the prism. Modern spectrophotometers more often employ diffraction gratings rather then prisms, and use electronic sensors connected to a computer. |

[image: Purdue U.] |

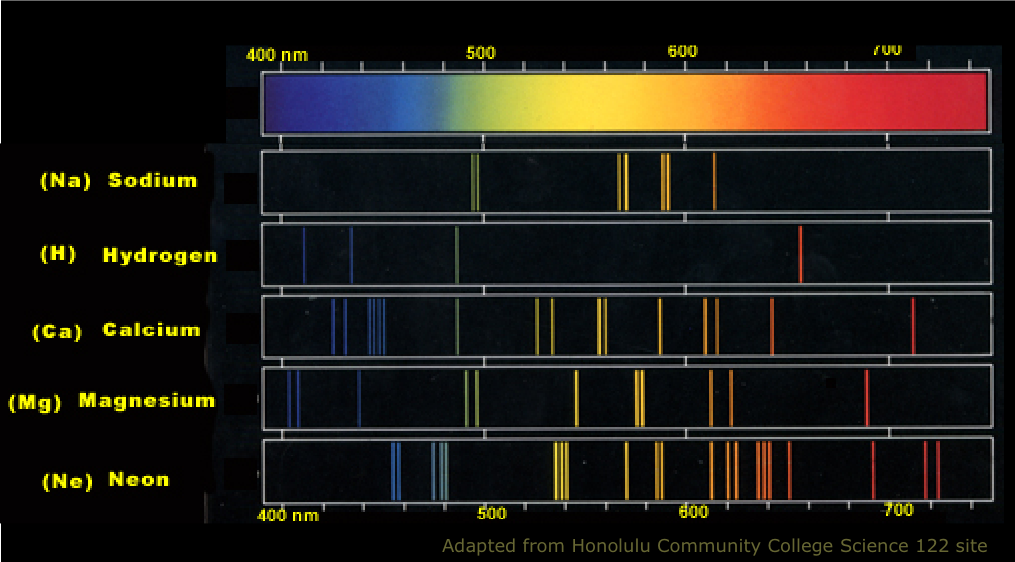

Each chemical element has its own characteristic emission line spectrum which serves as a "fingerprint" capable of identifying a particular element in a complex mixture. Shown below is what you would see if you could look at several different atomic line spectra directly.

What do these spectra tell us about the nature of chemical atoms? We will explore this question in some detail in the next lesson.

![]() Atomic line spectra are extremely useful for identifying small quantities of different elements in a mixture.

Atomic line spectra are extremely useful for identifying small quantities of different elements in a mixture.

- Companies that own large fleets of trucks and buses regularly submit their crankcase engine oil samples to spectrographic analysis. If they find high levels of certain elements (such as vanadium) that occur only in certain alloys, this can signal that certain parts of the engine are undergoing severe wear. This allows the mechanical staff to take corrective action before engine failure occurs.

- Several elements (Rb, Cs, Tl) were discovered by observing spectral lines that did not correspond to any of the then-known elements. Helium, which is present only in traces on Earth, was first discovered by observing the spectrum of the Sun.

- A more prosaic application of atomic spectra is determination of the elements present in stars.

Line spectra of discharge lamps and neon signs

If you live in a city, you probably see atomic line light sources every night! "Neon" signs are the most colorful and spectacular, but high-intensity street lighting is the most widespread source. A look at the emission spectrum (above) of sodium explains the intense yellow color of these lamps. The spectrum of mercury (not shown) similarly has its strongest lines in the blue-green region.

If you live in a city, you probably see atomic line light sources every night! "Neon" signs are the most colorful and spectacular, but high-intensity street lighting is the most widespread source. A look at the emission spectrum (above) of sodium explains the intense yellow color of these lamps. The spectrum of mercury (not shown) similarly has its strongest lines in the blue-green region.

About high-intensity discharge lamps

Neon signs: their history and how they work

The wavelength of a particle

de Broglie's name is widely mis-pronounced. The "g" is silent; "de-broy" is reasonably close.

There is one more fundamental concept you need to know before we can get into the details of atoms and their spectra. If light has a particle nature, why should particles not possess wavelike characteristics? In 1923 a young French physicist, Louis de Broglie, published an argument showing that matter should indeed have a wavelike nature. The de Broglie wavelength of a body, denoted by λ (lambda) is inversely proportional to its momentum mv:

If you explore the magnitude of the quantities in this equation (recall that h is around 10–33 J s), it will be apparent that the wavelengths of all but the lightest bodies are insignificantly small fractions of their dimensions, so that the objects of our everyday world all have definite boundaries. Even individual atoms are sufficiently massive that their wave character is not observable in most kinds of experiments.

Electrons, however, are another matter; the electron was in fact the first particle whose wavelike character was seen experimentally, following de Broglie's prediction. Its small mass (9.1E–31 kg) made it an obvious candidate, and velocities of around 100 km/s are easily obtained, yielding a value of λ in the above equation that well exceeds what we think of as the "radius" of the electron. At such velocities the electron behaves as if it is "spread out" to atomic dimensions; a beam of these electrons can be diffracted by the ordered rows of atoms in a crystal in much the same way as visible light is diffracted by the closely-spaced groves of a CD recording.

Some examples of de Broglie wavelength calculations

Electron diffraction has become an important tool for investigating the structures of molecules and of solid surfaces.

A more familiar exploitation of the wavelike properties of electrons is seen in the electron microscope, whose utility depends on the fact that the wavelength of the electrons is much less than that of visible light, thus allowing the electron beam to reveal detail on a correspondingly smaller scale.

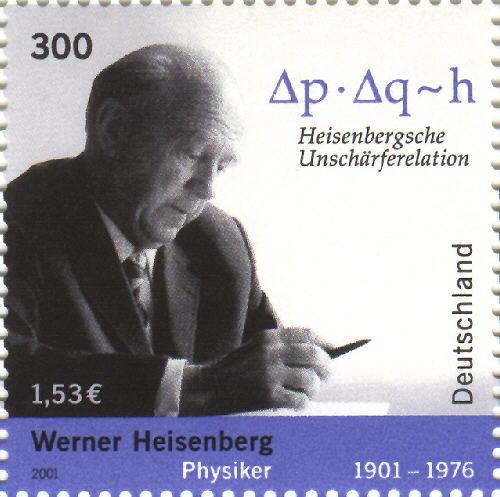

The uncertainty principle

In 1927, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg pointed out that the wave nature of matter leads to a profound and far-reaching conclusion: no method of observation, however perfectly it is carried out, can reveal both the exact location and momentum (and thus the velocity) of a particle.

In 1927, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg pointed out that the wave nature of matter leads to a profound and far-reaching conclusion: no method of observation, however perfectly it is carried out, can reveal both the exact location and momentum (and thus the velocity) of a particle.

Suppose that you wish to measure the exact location of a particle that is at rest (zero momentum). To accomplish this, you must "see" the molecule by illuminating it with light or other radiation. But the light acts like a beam of photons, each of which possesses the momentum h/λ in which λ is the wavelength of the light. When a photon collides with the particle, it transfers some of its momentum to the particle, thus altering both its position and momentum.

This is the origin of the widely known concept that the very process of observation will change the value of the quantity being observed. The Heisenberg principle can be expressed mathematically by the inequality

in which the δ's (deltas) represent the uncertainties with which the location and momentum are known. Notice how the form of this expression predicts that if the location of an object is known exactly (δx = 0), then the uncertainty in the momentum must be infinite, meaning that nothing at all about the velocity can be known. Similarly, if the velocity were specified exactly, then the location would be entirely uncertain and the particle could be anywhere.

One interesting consequence of this principle is that even at a temperature of absolute zero, the molecules in a crystal must still possess a small amount of zero point vibrational motion, sufficient to limit the precision to which we can measure their locations in the crystal lattice. An equivalent formulation of the uncertainty principle relates the uncertainties associated with a measurement of the energy of a system to the time δt taken to make the measurement:

The "uncertainty" referred to here goes much deeper than merely limiting our ability to observe the quantity δxδp to a greater precision than h/2π. It means, rather, that this product has no exact value, nor, by extension, do position and momentum on a microscopic scale. A more appropriate term would be indeterminacy, which is closer to Heisenberg's original word Ungenauigkeit.

Two well-done non-technical discussions of the uncertainty prinicple:

The American Institute of Physics "exhibit" of the HUP

The uncertainty principle in popular culture

The revolutionary nature Heisenberg's uncertainty principle now extends far beyond the arcane world of physics; the term has entered the realm of ideas and has inspired numerous creative works in the arts. But few of these really have much to do with Heisenberg's concept. [Zazzle T-shirt] →

The revolutionary nature Heisenberg's uncertainty principle now extends far beyond the arcane world of physics; the term has entered the realm of ideas and has inspired numerous creative works in the arts. But few of these really have much to do with Heisenberg's concept. [Zazzle T-shirt] →

Perhaps the best known of these is Michael Frayn's widely acclaimed 1998 play Copenhagen that is based on a secret meeting between Heisenberg and Niels Bohr in German-occupied Denmark during the second world war.

About the play Copenhagen - commentary on the play - DVD of the 2002 film