The basic gas laws

How P, V, and T are related

The "pneumatic" era of chemistry began with the discovery of the vacuum around 1650 which clearly established that gases are a form of matter. The ease with which gases could be studied soon led to the discovery of numerous empirical (experimentally-discovered) laws that proved fundamental to the later development of chemistry and led indirectly to the atomic view of matter. These laws are so fundamental to all of natural science and engineering that everyone learning these subjects needs to be familiar with them.

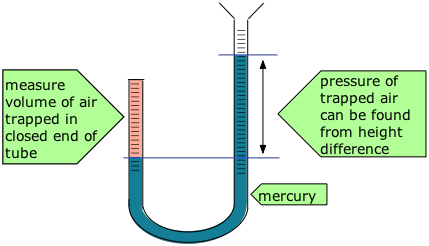

Robert Boyle (1627-91) showed that the volume of air trapped by a liquid in the closed short limb of a J-shaped tube decreased in exact proportion to the pressure produced by the liquid in the long part of the tube. The trapped air acted much like a spring, exerting a force opposing its compression. Boyle called this effect “the spring of the air", and published his results in a pamphlet of that title.

Robert Boyle (1627-91) showed that the volume of air trapped by a liquid in the closed short limb of a J-shaped tube decreased in exact proportion to the pressure produced by the liquid in the long part of the tube. The trapped air acted much like a spring, exerting a force opposing its compression. Boyle called this effect “the spring of the air", and published his results in a pamphlet of that title.

| volume | pressure | P × V |

|---|---|---|

| 96.0 | 2.00 | 192 |

| 76.0 | 2.54 | 193 |

| 46.0 | 4.20 | 193 |

| 26.0 | 7.40 | 193 |

Some of Boyle's actual data are shown in the table.

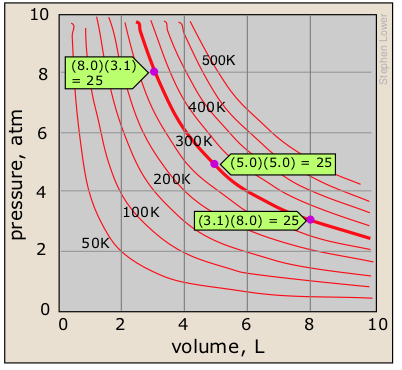

Boyle's law states that the pressure of a gas, held at a constant temperature, varies inversely with its volume:

PV = constant (1-1) must know!

or, equivalently,

P1V1 = P2V2 (1-2)

Boyle's law is a relation of inverse proportionality; any change in the pressure is exactly compensated by an opposing change in the volume. As the pressure decreases toward zero, the volume will increase without limit. Conversely, as the pressure is increased, the volume decreases, but can never reach zero. There will be a separate P-V plot for each temperature; a single P-V plot is therefore called an isotherm.

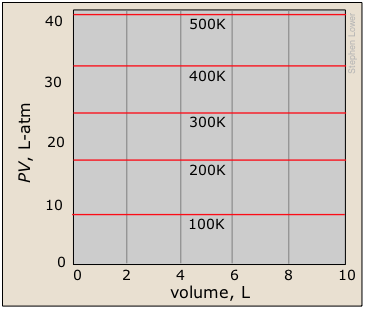

A related type of plot with which you should be familiar shows the product PV as a function of the pressure. You should understand why this yields a straight line, and how this set of plots relates to the one immediately above.

Charles' law

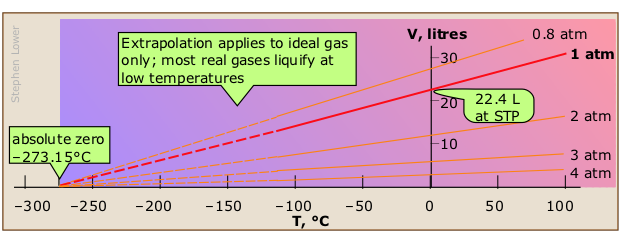

All matter expands when heated, but gases are special in that their degree of expansion is independent of their composition. In 1802, the French scientist Joseph Gay-Lussac (right, 1778-1850) found that if the pressure is held constant, the volume of any gas changes by the same fractional amount (1/273 of its value) for each C° change in temperature.

All matter expands when heated, but gases are special in that their degree of expansion is independent of their composition. In 1802, the French scientist Joseph Gay-Lussac (right, 1778-1850) found that if the pressure is held constant, the volume of any gas changes by the same fractional amount (1/273 of its value) for each C° change in temperature.

On learning that another scientist, Jacques Charles, had observed the proportionality between the volume and temperature of a gas 15 years earlier but had never published his findings, Gay-Lussac generously acknowledged this fact. Eventually, the "law of Charles and Gay-Lussac" become commonly known simply as "Charles' law".

V/T = constant or V1/T1 = V2 /T2 (be sure you understand why these two equations are equivalent!)

Historical notes

The fact that a gas expands when it is heated has long been known. In 1702, Guillaume Amontons (1163-1705), who is better known for his early studies of friction, devised a thermometer that related the temperature to the volume of a gas. Robert Boyle had observed this relationship in 1662, but the lack of any uniform temperature scale at the time prevented them from establishing the relationship as we presently understand it.

Jacques Charles discovered the law that is named for him in the 1780s, but did not publish his work. John Dalton published a form of the law in 1801, but the first thorough published presentation was made by Gay-Lussac in 1802, who acknowledged Charles' earlier studies.

Hot-air balloons and Charles' Law

The buoyancy that lifts a hot-air balloon into the sky depends on the difference between the density (mass ÷ volume) of the air entrapped within the balloon's envelope, compared to that of the air surrounding it. When a balloon on the ground is being prepared for flight, it is first partially inflated by an external fan, and possesses no buoyancy at all. Once the propane burners are started, this air begins to expand according to Charles' law. After the warmed air has completely inflated the balloon, further expansion simply forces excess air out of the balloon, leaving the weight of the diminished mass of air inside the envelope smaller than that of the greater mass of cooler air that the balloon displaces.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Jacques Charles collaborated with the Montgolfier Brothers whose hot-air balloon made the world's first manned balloon flight in June, 1783 (left). Ten days later, Charles himself co-piloted the first hydrogen-filled balloon. Gay-Lussac (right), who had a special interest in the composition of the atmosphere, also saw the potential of the hot-air balloon, and in 1804 he ascended to a then-record height of 6.4 km. [images: Wikimedia]

Click on the green-outlined images to enlarge them

Jacques Charles' understanding of buoyancy led to his early interest in balloons and to the use of hydrogen as an inflating gas. His first flight was witnessed by a crowd of 40,000 which included Benjamin Franklin, at that time ambassador to France. On its landing in the countryside, the balloon was reportedly attacked with axes and pitchforks by terrified peasants who believed it to be a monster from the skies. Charles' work was mostly in mathematics, but he managed to invent a number of scientific instruments and confirmed experiments in electricity that had been performed earlier by Benjamin Franklin and others.[*]

Gay-Lussac's balloon flights enabled him to sample the composition of the atmosphere at different altitudes (he found no difference). His Law of Combining Volumes (described below) constituted one of the foundations of modern chemistry. Gay-Lussac's contributions to chemistry are numerous; his work in electrochemistry enabled him to produce large quantities of sodium and potassium; the availability of these highly active metals led to his co-discovery of the element boron. He was also the the first to recognize iodine as an element. In an entirely different area, he developed a practical method of measuring the alcohol content of beverages, and coined the names "pipette" and "burette" that are known to all chemistry students. A good biography can be viewed at Google Books.

Gay-Lussac's balloon flights enabled him to sample the composition of the atmosphere at different altitudes (he found no difference). His Law of Combining Volumes (described below) constituted one of the foundations of modern chemistry. Gay-Lussac's contributions to chemistry are numerous; his work in electrochemistry enabled him to produce large quantities of sodium and potassium; the availability of these highly active metals led to his co-discovery of the element boron. He was also the the first to recognize iodine as an element. In an entirely different area, he developed a practical method of measuring the alcohol content of beverages, and coined the names "pipette" and "burette" that are known to all chemistry students. A good biography can be viewed at Google Books.

If you ever visit Paris, look for a street and a hotel near the Sorbonne that bear Gay-Lussac's name.

Gay-Lussac's Law of Combining Volumes

For a good tutorial overview of the Law of Combining Volumes, see this ChemPaths page.

In the same 1808 article in which Gay-Lussac published his observations on the thermal expansion of gases, he pointed out that when two gases react, they do so in volume ratios that can always be expressed as small whole numbers. This came to be known as the Law of combining volumes.

These "small whole numbers" are of course the same ones that describe the "combining weights" of elements to form simple compounds, as described in the lesson dealing with simplest formulas from experimental data.

Amadeo Avogadro

Amadeo Avogadro

The Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro (1776-1856) drew the crucial conclusion: these volume ratios must be related to the relative numbers of molecules that react, and thus the famous "E.V.E.N principle":

Equal volumes of gases, measured at the same temperature and pressure, contain equal numbers of molecules

Avogadro's law thus predicts a directly proportional relation between the number of moles of a gas and its volume.

This relationship, originally known as Avogadro's Hypothesis, was crucial in establishing the formulas of simple molecules at a time (around 1811) when the distinction between atoms and molecules was not clearly understood. In particular, the existence of diatomic molecules of elements such as H2, O2, and Cl2 was not recognized until the results of combining-volume experiments such as those depicted below could be interpreted in terms of the E.V.E.N. principle.

How the E.V.E.N. principle led to the correct formula of water

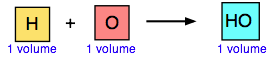

Early chemists made the mistake of assuming that the formula of water is HO. This led them to miscalculate the molecular weight of oxygen as 8 (instead of 16). If this were true, the reaction H + O → HO would correspond to the following combining volumes results according to the E.V.E.N principle:

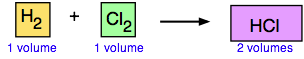

But a similar experiment on the formation of hydrogen chloride from hydrogen and chlorine yielded twice the volume of HCl that was predicted by the the assumed reaction H + Cl → HCl. This could be explained only if hydrogen and chlorine were diatomic molecules:

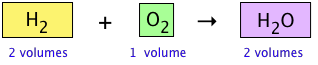

This made it necessary to re-visit the question of the formula of water. The experiment immediately confirmed that the correct formula of water is H2O:

This conclusion was also seen to be consistent with the observation, made a few years earlier by the English chemists Nicholson and Carlisle that the reverse of the above reaction, brought about by the electrolytic decomposition of water, yields hydrogen and oxygen in a 2:1 volume ratio.

A nice overview of these developments can be seen at David Dice's Chemistry page, from which this illustration is taken.

If the variables P, V, T and n (the number of moles) have known values, then a gas is said to be in a definite state, meaning that all other physical properties of the gas are also defined. The relation between these state variables is known as an equation of state. By combining the expressions of Boyle's, Charles', and Avogadro's laws (you should be able to do this!) we can write the very important ideal gas equation of state

where the proportionality constant R is known as the gas constant. This is one of the few equations you must commit to memory in this course; you should also know the common value and units of R.

Take note of the word "hypothetical" here. No real gas (whose molecules occupy space and interact with each other) can behave in a truly ideal manner. But we will see in the last lesson of this series that all gases behave more and more like an ideal gas as the pressure approaches zero. A pressure of only 1 atm is sufficiently close to zero to make this relation useful for most gases at this pressure.

Many textbooks show formulas, such as P1V1 = P2V2 for Boyle's law. Don't bother memorizing them; if you really understand the meanings of these laws as stated above, you can easily derive them on the rare occasions when they are needed. The ideal gas equation is the only one you need to know.

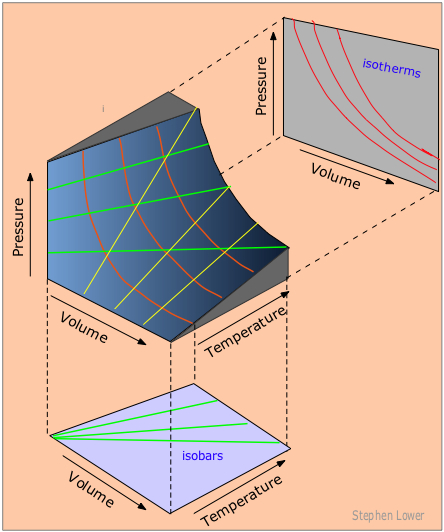

PVT surface for an ideal gas

In order to depict the relations between the three variables P, V and T we need a three-dimensional graph.

Each point on the curved surface represents a possible combination of (P,V,T) for an arbitrary quantity of an ideal gas. The three sets of lines inscribed on the surface correspond to states in which one of these three variables is held constant.

The red curved lines, being lines of constant temperature, or isotherms, are plots of Boyle's law. These isotherms are also seen projected onto the P-V plane at the top right.

The yellow lines are isochors and represent changes of the pressure with temperature at constant volume.

The green lines, known as isobars, and projected onto the V-T plane at the bottom, show how the volumes contract to zero as the absolute temperature approaches zero, in accordance with the law of Charles and Gay-Lussac.