Chemical equilibrium: Introduction

Reactions that go both ways

Chemical change is one of the two central concepts of chemical science, the other being structure. The very origins of Chemistry itself are rooted in the observations of transformations such as the combustion of wood, the freezing of water, and the winning of metals from their ores that have always been a part of human experience. It was, after all, the quest for some kind of constancy underlying change that led the Greek thinkers of around 200 BCE to the idea of elements and later to that of the atom.

It would take almost 2000 years for the scientific study of matter to pick up these concepts and incorporate them into what would emerge, in the latter part of the 19th century, as a modern view of chemical change.

Chemical change occurs when the atoms that make up one or more reactants rearrange themselves in such a way that new substances, called products, are formed. The reactants and products are the components of the chemical reaction system.

A given chemical reaction system is defined by a balanced net chemical equation which is conventionally written as

reactants → products

The first thing we need to know about a chemical reaction represented by a balanced equation is whether it can actually take place. If the reactants and products are all substances capable of an independent existence, then in principle, the answer is always "yes". This answer must be qualified, however, by the following considerations:

- How complete is the reaction?

- That is, what fraction of the reactants are converted into products? Some reactions convert essentially 100% of reactants to products, while for others the quantity of products may be undetectable. Many are somewhere in between, meaning that significant quantities of all components remain at the end. Later on, in another part of the course, you will learn that the tendency of a reaction to occur can be predicted entirely from the properties of the reactants and products through the laws of thermodynamics.

- How fast does the reaction occur?

- Some reactions are over in microseconds; others take years. The speed of any one reaction can vary over a huge range depending on the temperature, the state of matter (gas, liquid, solid) and the presence of a catalyst. Unlike the question of completeness, there is no simple way of predicting reaction speed.

- What is the mechanism of the reaction?

- What happens, at the atomic or molecular level, when reactants are transformed into products? What intermediate species (those that are produced but later consumed so that they do not appear in the net reaction equation) are involved? This is the microscopic, or kinetic view of chemical change, and cannot be predicted by theory as it is presently developed and must be inferred from the results of experiments.

A reaction that is thermodynamically possible but for which no reasonably rapid mechanism is available is said to be kinetically limited. Conversely, one that occurs rapidly but only to a small extent is thermodynamically limited. As you will see later, there are often ways of getting around both kinds of limitations, and their discovery and practical applications constitute an important area of industrial chemistry.

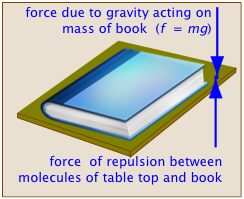

Basically, the term refers to what we might call a "balance of forces". In the case of mechanical equilibrium, this is its literal definition. A book sitting on a table top remains at rest because the downward force exerted by the earth's gravity acting on the book's mass (this is what is meant by the "weight" of the book) is exactly balanced by the repulsive force between atoms that prevents two objects from simultaneously occupying the same space, acting in this case between the surfaces of the table and the book. If you pick up the book and raise it above the table top, the additional upward force exerted by your arm destroys the state of equilibrium as the book moves upward. If you wish to hold the book at rest above the table, you adjust the upward force to exactly balance the weight of the book, thus restoring equilibrium.

Basically, the term refers to what we might call a "balance of forces". In the case of mechanical equilibrium, this is its literal definition. A book sitting on a table top remains at rest because the downward force exerted by the earth's gravity acting on the book's mass (this is what is meant by the "weight" of the book) is exactly balanced by the repulsive force between atoms that prevents two objects from simultaneously occupying the same space, acting in this case between the surfaces of the table and the book. If you pick up the book and raise it above the table top, the additional upward force exerted by your arm destroys the state of equilibrium as the book moves upward. If you wish to hold the book at rest above the table, you adjust the upward force to exactly balance the weight of the book, thus restoring equilibrium.

An object is in a state of mechanical equilibrium when it is either static (motionless) or in a state of unchanging motion. From the relation f = ma, it is apparent that if the net force on the object is zero, its acceleration must also be zero, so if we can see that an object is not undergoing a change in its motion, we know that it is in mechanical equilibrium.

An object is in a state of mechanical equilibrium when it is either static (motionless) or in a state of unchanging motion. From the relation f = ma, it is apparent that if the net force on the object is zero, its acceleration must also be zero, so if we can see that an object is not undergoing a change in its motion, we know that it is in mechanical equilibrium.

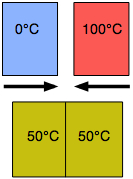

Thermal equilibrium

Another kind of equilibrium we all experience is thermal equilibrium. When two objects are brought into contact, heat will flow from the warmer object to the cooler one until their temperatures become identical. Thermal equilibrium arises from the tendency of thermal energy to become as dispersed or "diluted" as possible.

A metallic object at room temperature will feel cool to your hand when you first pick it up because the thermal sensors in your skin detect a flow of heat from your hand into the metal, but as the metal approaches the temperature of your hand, this sensation diminishes. The time it takes to achieve thermal equilibrium depends on how readily heat is conducted within and between the objects; thus a wooden object will feel warmer than a metallic object even if both are at room temperature because wood is a relatively poor thermal conductor and will therefore remove heat from your hand more slowly.

Thermal equilibrium is something we often want to avoid, or at least postpone; this is why we insulate buildings, perspire in the summer and wear heavier clothing in the winter.

Chemical equilibrium

When a chemical reaction takes place in a container which prevents the entry or escape of any of the substances involved in the reaction, the quantities of these components change as some are consumed and others are formed. Eventually this change will come to an end, after which the composition will remain unchanged as long as the system remains undisturbed. The system is then said to be in its equilibrium state, or more simply, "at equilibrium".

Equilibrium and closed systems

Reactions that take place in open systems will not be reversible if products can escape.

Reactions that take place in open systems will not be reversible if products can escape.

It is important to bear in mind that equilibrium can only be achieved if none of the reactants or products is allowed to escape from the system; such a system is said to be closed. As a simple example, consider the vaporization of water:

H2O(l) → H2O(g)

If some water is placed in a closed container, the partial pressure of water vapor in the space above the liquid will gradually build up to a constant (equilibrium) value which depends mainly on the temperature. But if the water is left to vaporize in the open, the water vapor will simply be dispersed into the environment, the system is open and the equilibrium state will never be reached.

Why reactions go toward equilibrium

What is the nature of the "balance of forces" that drives a reaction toward chemical equilibrium? It is essentially the balance struck between the tendency of energy to reside within the chemical bonds of stable molecules, and its tendency to become dispersed and diluted. Exothermic reactions are particularly effective in this, because the heat released gets dispersed in the infinitely wider world of the surroundings.

What is the nature of the "balance of forces" that drives a reaction toward chemical equilibrium? It is essentially the balance struck between the tendency of energy to reside within the chemical bonds of stable molecules, and its tendency to become dispersed and diluted. Exothermic reactions are particularly effective in this, because the heat released gets dispersed in the infinitely wider world of the surroundings.

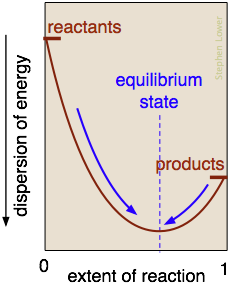

In the reaction represented here, this balance point occurs when about 60% of the reactants have been converted to products. Once this equilibrium state has been reached, no further net change will occur. (The only spontaneous changes that are allowed follow the arrows pointing toward maximum dispersal of energy.)

A more complete explanation of this must be deferred until the discussion of thermodynamics in a later chapter.

Chemical equilibrium is something you definitely want to avoid for yourself as long as possible. The myriad chemical reactions in living organisms are constantly moving toward equilibrium, but are prevented from getting there by input of reactants and removal of products. So rather than being in equilibrium, we try to maintain a "steady-state" condition which physiologists call homeostasis — maintenance of a constant internal environment. For more on this, see this Wikipedia article. Equilibrium is death!

Chemical equilibrium is something you definitely want to avoid for yourself as long as possible. The myriad chemical reactions in living organisms are constantly moving toward equilibrium, but are prevented from getting there by input of reactants and removal of products. So rather than being in equilibrium, we try to maintain a "steady-state" condition which physiologists call homeostasis — maintenance of a constant internal environment. For more on this, see this Wikipedia article. Equilibrium is death!

For the time being, it's very important that you know this definition:

The direction in which we write a chemical reaction (and thus which components are considered reactants and which are products) is arbitrary. Thus the two equations

| H2 + I2 → 2 HI | "synthesis of hydrogen iodide" |

| 2 HI → H2 + I2 | "dissociation of hydrogen iodide" |

represent the same chemical reaction system in which the roles of the components are reversed, and both yield the same mixture of components when the change is completed.

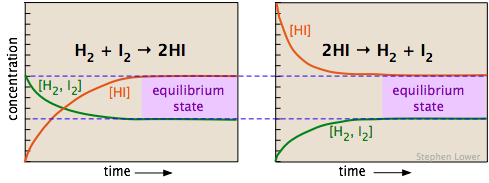

This last point is central to the concept of chemical equilibrium. It makes no difference whether we start with two moles of HI or one mole each of H2 and I2; once the reaction has run to completion, the quantities of these two components will be the same. In general, then, we can say that the composition of a chemical reaction system will tend to change in a direction that brings it closer to its equilibrium composition. Once this equilibrium composition has been attained, no further change in the quantities of the components will occur as long as the system remains undisturbed.

It's the same both ways

The two diagrams below show how the concentrations of the three components of this chemical reaction change with time. Examine the two sets of plots carefully, noting which substances have zero initial concentrations, and are thus "products" of the reaction equations shown. Satisfy yourself that these two sets represent the same chemical reaction system, but with the reactions occurring in opposite directions. Most importantly, note how the final (equilibrium) concentrations of the components are the same in the two cases.

Whether we start with an equimolar mixture of H2 and I2 (left) or a pure sample of hydrogen iodide (shown on the right, using twice the initial concentration of HI to keep the number of atoms the same), the composition after equilibrium is attained (shaded regions on the right) will be the same.

A chemical equation of the form A → B represents the transformation of A into B, but it does not imply that all of the reactants will be converted into products, or that the reverse reaction B → A cannot also occur.

In general, both processes (forward and reverse) can be expected to occur, resulting in an equilibrium mixture containing finite amounts of all of the components of the reaction system. (We use the word components when we do not wish to distinguish between reactants and products.)

If the equilibrium state is one in which significant quantities of both reactants and products are present (as in the hydrogen iodide example given above), then the reaction is said to be incomplete or reversible.

The latter term is preferable because it avoids confusion with "complete" in its other sense of being completed or finished, implying that the reaction has run its course and is now at equilibrium.

- If it is desired to emphasize the reversibility of a reaction, the single arrow in the equation is replaced with a pair of hooked lines pointing in opposite directions, as in A

B.

B. - A reaction is said to be complete or quantitative when the equilibrium composition contains no significant amount of the reactants. A reaction that is complete when written in one direction is said "not to occur" when written in the reverse direction.

Note that there is no fundamental difference between the meanings of A → B and A ![]() B. Some older textbooks just use A = B.

B. Some older textbooks just use A = B.

In principle, all "elementary" (simple one-step) chemical reactions are reversible, but this reversibility may not be observable if the fraction of products in the equilibrium mixture is very small, or if the reverse reaction is very slow (the chemist's term is "kinetically inhibited")

Why some reactions are not reversible

Chemical changes that take place in multiple steps, and thus involve many different reactions, tend to be irreversible; "you can't put Humpty Dumpty together again". But even relatively simple reactions can be almost impossible to reverse if the thermodynamic stability of the products is far greater than that of the reactants.

Here are some examples of irreversible reactions that we all see in our daily lives:

- The chemistry of combustion and flames is hugely complicated, with different processes taking place in different parts of the flame. There is no way you can

"un-burn" a combustible object! - Heating egg-white causes its proteins to unfold into a permanently entangled mess. (More here.)

- Corrosion of iron results in the formation of a number of iron oxides that are more stable than iron itself; there is no going back!

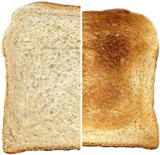

- Browning of toast (and of meats) is the result of the Maillard reaction in which amino acids (from the protein material) combine with certain types of sugars to produce a large variety of brown (and flavorful) complex products.

How did Napoleon Bonaparte help discover reversible reactions?

We can thank Napoleon for bringing the concept of reaction reversibility to Chemistry.

We can thank Napoleon for bringing the concept of reaction reversibility to Chemistry.

Napoleon recruited the eminent French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet (1748-1822) to accompany him as scientific advisor on the most far-flung of his campaigns, the expedition into Egypt in 1798. Once in Egypt, Berthollet noticed deposits of sodium carbonate around the edges of some the salt lakes found there. He was already familiar with the reaction

Na2CO3 + CaCl2 → CaCO3 + 2 NaCl

which was known to proceed to completion in the laboratory. He immediately realized that the Na2CO3 must have been formed by the reverse of this process brought about by the very high concentration of salt in the slowly-evaporating waters. This led Berthollet to question the belief of the time that a reaction could only proceed in a single direction. His famous textbook Essai de statique chimique (1803) presented his speculations on chemical affinity and his discovery that an excess of the product of a reaction could drive it in the reverse direction.

which was known to proceed to completion in the laboratory. He immediately realized that the Na2CO3 must have been formed by the reverse of this process brought about by the very high concentration of salt in the slowly-evaporating waters. This led Berthollet to question the belief of the time that a reaction could only proceed in a single direction. His famous textbook Essai de statique chimique (1803) presented his speculations on chemical affinity and his discovery that an excess of the product of a reaction could drive it in the reverse direction.

Unfortunately, Berthollet got a bit carried away by the idea that a reaction could be influenced by the amounts of substances present, and maintained that the same should be true for the compositions of individual compounds. This brought him into conflict with the recently accepted Law of Definite Proportions (that a compound is made up of fixed numbers of its constituent atoms), so his ideas (the good along with the bad) were promptly discredited and remained largely forgotten for 50 years. (Ironically, it is now known that certain classes of compounds do in fact exhibit variable composition of the kind that Berthollet envisioned.)

The law of mass action

Berthollet's ideas about reversible reactions were finally vindicated by experiments carried out by others, most notably the Norwegian chemists (and brothers-in-law) Cato Guldberg and Peter Waage. During the period 1864-1879 they showed that an equilibrium can be approached from either direction.

Recall the example in Section 2 above, in which the reactionsH2 + I2 → 2HI and

2HI → H2 + I2, when carried out under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, yield the same equilibrium concentrations of the three gases.

If we wish to emphasize this fact, we can express this process by the single equation H2 + I2 ![]() 2HI.

2HI.

More generally, we can consider that any reversible reaction of the form

aA + bB → cC + dD is really a competition between a "forward" and a "reverse" reaction. When a reaction is at equilibrium, the rates of these two reactions are identical, so no net (macroscopic) change is observed, although individual components are actively being transformed at the microscopic level.

Equilibrium is dynamic !

Guldberg and Waage showed that for a reaction aA + bB → cC + dD,

the rate (speed) of the reaction in either direction is proportional to what they called the "active masses" (concentrations) of the various components:

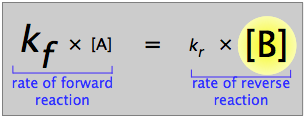

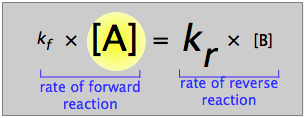

rate of forward reaction = kf [A]a [B]b

rate of reverse reaction = kr [C]c [D]d

in which the proportionality constants k are called rate constants and the quantities in square brackets represent concentrations. If we combine the two reactants A and B, the forward reaction starts immediately; then, as the products C and D begin to build up, the reverse process gets underway. As the reaction proceeds, the rate of the forward reaction diminishes while that of the reverse reaction increases. Eventually the two processes are proceeding at the same rate, and the reaction is at equilibrium:

rate of forward reaction = rate of reverse reaction

kf [A]a [B]b = kr [C]c [D]d

It is very important that you understand the significance of this relation. The equilibrium state is one in which there is no net change in the quantities of reactants and products. But do not confuse this with a state of "no change"; at equilibrium, the forward and reverse reactions continue, but at identical rates, essentially cancelling each other out.

To further illustrate the dynamic character of chemical equilibrium, suppose that we now change the composition of the system previously at equilibrium by adding some C or withdrawing some A (thus changing their "active masses"). The reverse rate will temporarily exceed the forward rate and a change in composition ("a shift in the equilibrium") will occur until a new equilibrium composition is achieved.

The composition of the equilibrium state depends on the ratio of the forward- and reverse rate constants.

Be sure you understand the difference between the rate of a reaction and a rate constant.

The reaction rate is simply the "speed" of the reaction, expressed in units such as moles of product per second.

The rate constant, usually designated by k, relates the reaction rate to the concentration of one or more of the reaction components — for example,

rate = k [A].

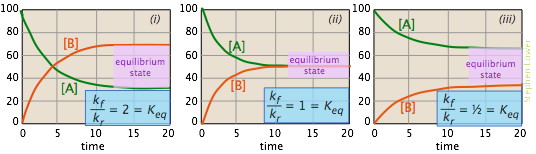

At equilibrium, the rates of the forward and reverse processes are identical, but the rate constants are generally different. To see how this works, consider the simplified reaction A → B in the following three scenarios.

- kf >> kr

If the rate constants are greatly different (by many orders of magnitude), then this requires that the equilibrium concentrations of products exceed those of the reactants by the same ratio. Thus the equilibrium composition will lie strongly on the "right"; the reaction can be said to be "complete" or "quantitative".

If the rate constants are greatly different (by many orders of magnitude), then this requires that the equilibrium concentrations of products exceed those of the reactants by the same ratio. Thus the equilibrium composition will lie strongly on the "right"; the reaction can be said to be "complete" or "quantitative".- kf << kr

The rates can only be identical (equilibrium achieved) if the concentrations of the products are very small. We describe the resulting equilibrium as strongly favoring the left; very little product is formed. In the most extreme cases, we might even say that "the reaction does not take place".

The rates can only be identical (equilibrium achieved) if the concentrations of the products are very small. We describe the resulting equilibrium as strongly favoring the left; very little product is formed. In the most extreme cases, we might even say that "the reaction does not take place".- kf ≈ kr

- If kf and kr have comparable values (within, say, several orders of magnitude), then signficant concentrations of products and reactants are present at equilibrium; we say the the reaction is "incomplete" and "reversible".

The images shown below offer yet another way of looking at these three cases. The plots show how the relative concentrations of the reactant and product change during the course of the reaction.

- In plot (i) the forward rate constant is twice as large as the reverse rate constant, so product (B) is favored, but there is sufficient reverse reaction to maintain a significant quantity of A.

- In (ii), the forward and reverse rate constants have identical magnitudes. Not surprisingly, so are the equilibrium values of [A] and [B].

- In (iii), the reverse rate constant exceeds the forward rate constant, so the eqilibrium composition is definitely "on the left".

The Law of Mass Action is thus essentially the statement that the equilibrium composition of a reaction mixture can vary according to the quantities of components that are present. This of course is just what Berthollet observed in his Egyptian salt ponds, but we now understand it to be a consequence of the dynamic nature of chemical equilibrium.

Clearly, if we observe some change taking place— a change in color, the release of gas bubbles, the appearance of a precipitate, or the release of heat, we know the reaction is not yet at equilibrium.

But the absence of any apparent change does not by itself establish that the reaction is at equilibrium. The equilibrium state is one in which not only no change in composition take place, but also one in which no energetic tendency for further change is present. Unfortunately, "tendency" is not a property that is directly observable! Consider, for example, the reaction representing the synthesis of water from its elements:

2 H2(g) + O2(g)→ 2 H2O(g)

You can store hydrogen and oxygen in the same container indefinitely without any observable change occurring. But if you create an electrical spark in the container or introduce a flame, bang! After you pick yourself up off the floor and remove the shrapnel from what's left of your body, you will know very well that the system was not initially at equilibrium! It happens that this particular reaction has a tremendous tendency to take place, but for reasons that we will discuss in a later chapter, nothing can happen until we "set it off" in some way— in this case by exposing the mixture to a flame or spark, or (in a more gentle way) by introducing a platinum wire, which acts as a catalyst.

A reaction of this kind is said to be highly favored thermodynamically, but inhibited kinetically.

Another interesting kinetically-inhibited reaction is the one between hydrogen and chlorine to form hydrogen chloride:

H2(g)+ Cl2(g)→ 2 HCl(g)

If these two elements are mixed in the dark, nothing will happen, but exposure to light will cause them to combine almost instantaneously. This reaction, like most of its kind, is highly exothermic, and the release of so much heat in so short a time causes the HCl to expland explosively.

In contrast, the similar reaction of hydrogen and iodine vapor

H2(g)+ I2(g)→ 2 HI(g)

is only moderately favored thermodynamically (and is thus incomplete), but its kinetics are unspectacular.

Some simple tests for the equilibrium state

There are several ways of determining if a given reaction system is in equilibrium.

All of these assume that 1) the change in composition is accompanied by a change in some observable property (color, pressure, volume, etc.), and 2) the reaction is not so slow as to exhaust one's patience.

- As we explained above in the context of the law of mass action, addition or removal of one component of a system in equilibrium will affect the amounts of all the others. For example, if we add more of a reactant, we would expectthe concentration of a product change.

- It is almost always the case, however, that once a reaction actually starts, it will continue on its own until it reaches equilibrium, so if we can observe the change as it occurs and see it slow down and stop, we can be reasonably certain that the system is in equilibrium. This is by far the chemist's most common criterion.

- There is one other experimental test for equilibrium in a chemical reaction, although it is really only applicable to the kind of reactions we described above as being reversible. As we shall see later, the equilibrium state of a system is always sensitive to the temperature, and often to the pressure, so any changes in these variables, however, small, will temporarily disrupt the equilibrium, resulting in an observable change in the composition of the system as it moves toward its new equilibrium state.

Extremely slow reactions, whose rates are expressed in years or centuries, usually involving solids, do often present difficulties — mostly to geochemists, and occasionally to art conservators, who are often troubled by pigments of uncertain composition that may slowly decompose or react with the local environment.

- Define "the equilibrium state of a chemical reaction system". What is its practical significance?

- State the meaning and significance of the following terms:

- reversible reaction

- quantitative reaction

- kinetically inhibited reaction

- Explain the meaning of the statement "equilibrium is macroscopically static, but microscopically dynamic". Very important!

- Explain how the relatve magnitudes of the forward and reverse reaction rate constants in the Mass Action expression affect the equilibrium composition of a reaction system.

- Describe several things you might look for during an experiment that would help determine if a reaction system is in its equilibrium state.