Chem1 General Chemistry Virtual Textbook → acid-base equilibria - Strong acids and bases

Strong acids and bases

No calculations needed for moderate concentrations

On this page:

To a good approximation, strong acids, in the forms we encounter in the laboratory and in much of the industrial world, have no real existence; they are all really solutions of H3O+. So if you think about it, the labels on those reagent bottles you see in the lab are not strictly true!

To a good approximation, strong acids, in the forms we encounter in the laboratory and in much of the industrial world, have no real existence; they are all really solutions of H3O+. So if you think about it, the labels on those reagent bottles you see in the lab are not strictly true!

But if the strong acid is highly diluted, the amount of H3O+ it contributes to the solution becomes comparable to that which derives from the autoprotolysis of water. Under these conditions, we need to develop a more systematic way of working out equilibrium concentrations.

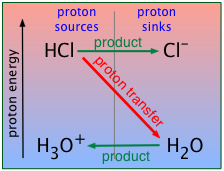

A strong acid, you will recall, is one that is stronger than the hydronium ion H3O+. This means that in the presence of water, the proton on a strong acid such as HCl will "fall" into the "sink" provided by H2O, converting the latter into its conjugate acid H3O+. In other words, H3O+ is the strongest acid that can exist in aqueous solution.

A strong acid, you will recall, is one that is stronger than the hydronium ion H3O+. This means that in the presence of water, the proton on a strong acid such as HCl will "fall" into the "sink" provided by H2O, converting the latter into its conjugate acid H3O+. In other words, H3O+ is the strongest acid that can exist in aqueous solution.

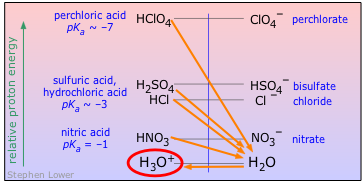

As we explained in the preceding lesson, all strong acids appear to be equally strong in aqueous solution because there are always plenty of H2O molecules to accept their protons. We called this the "leveling effect".

As we explained in the preceding lesson, all strong acids appear to be equally strong in aqueous solution because there are always plenty of H2O molecules to accept their protons. We called this the "leveling effect".

This greatly simplifies our treatment of stong acids because there is no need to deal with equilibria such as HCl + H2O → H3O+ + Cl–; the equilibrium constants for such reactions are so overwhelmingly large that we can usually consider the concentrations of acid species such as "HCl" to be indistinguishable from zero.

As we will see further on, this is not strictly true for highly-concentrated solutions of strong acids.

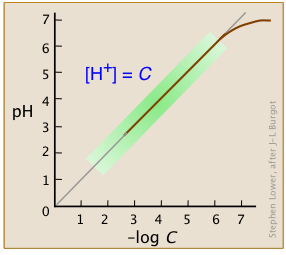

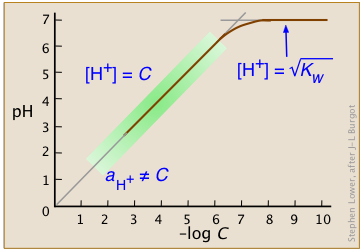

Over the normal range of concentrations we commonly work with (indicated by the green shading on this plot), the pH of a strong acid solution is given by the negative logarithm of its concentration in mol L–1.

Over the normal range of concentrations we commonly work with (indicated by the green shading on this plot), the pH of a strong acid solution is given by the negative logarithm of its concentration in mol L–1.

Note that in very dilute solutions, the plot levels off, showing that this simple relation breaks down; there is no way you can make the solution alkaline by diluting an acid!

What will be the pH of a 0.025 mol/l solution of hydrochloric acid?

Solution: Just find the negative logarithm of the concentration:

– log10 (0.025) = 1.6

| acid | name | pKa | base | pKb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HClO4 | perchloric acid | ~ –7 | ClO4– | ~ 21 |

| HCl | hydrochloric acid | ~ –7 | Cl– | ~ 17 |

| H2SO4 | sulfuric acid | ~ –7 | HSO4– | ~ 17 |

| HNO3 | nitric acid | –1 | NO3– | 15 |

| H3O+ | hydronium ion | H2O | 14 |

You should know the names and formulas of all four of these widely-encountered strong mineral acids.

Mineral acids are those that are totally inorganic. Not all mineral acids are strong; boric and carbonic acids are common examples of very weak ones. But in ordinary usage, the term often implies one of those described below.

With the exception of perchloric acid, which requires special handling, these are all widely used in industry and are almost always found in chemistry laboratories. Most have been known since ancient times.

Hydrochloric acid HCl

In contrast to the other strong mineral acids, no pure compound "hydrochloric acid" exists. One of the most commonly used acids, hydrochloric acid is usually sold as a constant-boiling 37% solution of hydrogen chloride gas in water, making its concentration about 10M. Although higher concentrations are possible, the high partial pressures of HCl in equilibrium with the solution makes them difficult to store, ship and work with.

Commercial-grade hydrochloric acid is often called muriatic acid.

Nitric acid, HNO3

Concentrated nitric acid is a 68% constant-boiling solution of HNO3 in water, corresponding to about 11M. Although the acid itself is colorless, its slow decomposition into NO2 (especially in the presence of light) often results in a yellow or orange color. More concentrated solutions are sold as "fuming nitric acid"; one form, available as "white fuming nitric acid" or "anhydrous nitricacid" contains 97.5% HNO3 and only 2% water; the remainder consists of dissolved NO2. Pure HNO3 forms crystals that melt at –42°C.

In addition to being a strong acid, nitric acid at high concentrations acts as a powerful oxidizing agent, a property that accounts for its use as a rocket fuel.

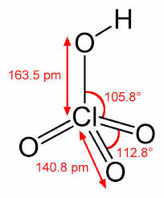

Perchloric acid HClO4

This is the strongest of the mineral acids, thanks to the electron-withdrawing action of the oxygen atoms which make it energetically easier for HClO4 to lose its proton. Its usual commercial form is a constant-boiling 72.5% solution in water.

Concentrated perchloric acid is a powerful oxidizing agent that can react explosively with organic materials and certain metals. Its use in the laboratory requires special handling. A 1947 explosion of a 1000-L vat of HClO4 in a Los Angeles electroplating plant killed 17 people and damaged over 250 homes and other buildings. (I recall hearing the "boom" when I was in my middle school at the time.)

Sulfuric acid H2SO4

Sulfuric acid is by far the most industrially important acid, and is also the most concentrated one available. "Concentrated" sulfuric acid contains 98% by weight of H2SO4; its density of 1.83 kg/L and oil-like viscosity reflect this high concentration.

"100% H2SO4" (which can be prepared but is not stable) actually contains a variety of other species, all in equilibrium with H2SO4. These include H2S2O7, H2S4O13, and H2SO4's autoprotolysis products H3SO4– and HSO4+.

Super acids

There is a class of super acids that are stronger than some of the common mineral acids. Some, like fluorosulfuric acid FSO3H are commercially available. The strongest known super acid is fluoroantimonic acid.

Strong bases

Solid NaOH is usually sold in the form of pellets. When exosed to air, they become wet (deliquescence) and absorb CO2, becoming contaminated with sodium carbonate.

The only strong bases that are commonly encountered are solutions of

Group 1 hydroxides, mainly NaOH and KOH. Unlike most metal hydroxides, these solids are highly soluble in water, and can thus yield concentrated solutions of hydroxide ion, the strongest base that can exist in water — the ultimate aquatic proton sink.

Sodium hydroxide is by far the most important of these strong bases; its common names "lye", "caustic soda" (or, in industry, often just "caustic"), reflect the diverse uses of NaOH.

NaOH is the most soluble of the Group 1 hydroxides, dissolving in less than its own weight of water (111 g / 100 ml) to form a 2.8 M/L solution at 20°C. But as with strong acids, the pH of such a solution cannot be reliably calculated from such a high concentration.

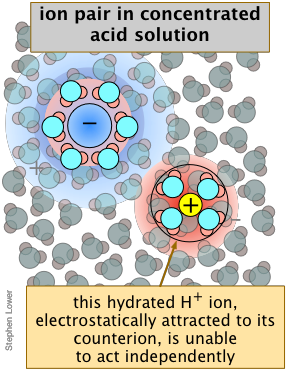

At higher concentrations, intermolecular interactions and ion-pairing can cause the effective concentration (known as the activity) of H3O+ to deviate from the value corresponding to the nominal or "analytical" concentration of the acid.

Mean ionic activity coefficient of HCl at 25° C

(Because activities of single ions cannot be measured, these mean values are the closest we can get to {H+} in solutions of strong acids.)

| molarity | γ± |

|---|---|

| .0005 | .975 |

| .01 | .904 |

| .10 | .796 |

| 1 | .809 |

| 2 | 1.01 |

| 5 | 2.38 |

| 10 | 10.44 |

Activities are important because only these work properly in equilibrium calculations. Also, pH is defined as the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion activity, not its concentration. The relation between the concentration of a species and its activity is expressed by the activity coefficient γ (gamma):

a = γC

As a solution becomes more dilute, γ approaches unity. At ionic concentrations not exceeding about 2M, concentrations of typical strong acids can generally be used in place of activities without serious error.

Note that activities of single ions other than H3O+ cannot be determined, so activity coefficients in ionic solutions are always the average, or mean, of those for the ionic species present. This quantity is denoted as γ±.

This is a practical consideration when dealing with strong mineral acids which are available at concentrations of 10M or greater.

In a 12 M solution of hydrochloric acid, for example, the mean ionic activity coefficient is 17.25. This means that under these conditions with [H3O+] = 12M, the activity {H3O+} = 12 × 17.25 = 207, corresponding to a pH of about –2.3, instead of –1.1 as might be predicted if concentrations were being used.

These very high activity coefficients also explain another phenomenon: why you can detect the odor of HCl(g) over a concentrated hydrochloric acid solution even though this acid is supposedly 100% dissociated. It turns out that the activity {HCl} (which represents the "escaping tendency" of HCl(g) from the solution) is almost 49,000 for a 10 M solution! The source of this gas is best described as the result of ion pairing.

Similarly, in a solution prepared by adding 0.5 mole of the very strong acid HClO4 to sufficient water to make the volume 1 liter, freezing-point depression measurements indicate that the concentrations of hydronium and perchlorate ions are only about 0.4 M. This does not mean that the acid is only 80% dissociated; there is no evidence of HClO4 molecules in the solution. What has happened is that about 20% of the H3O+ and ClO4– ions have formed ion-pair complexes in which the oppositely-charged species are loosely bound by electrostatic forces.

Ion-pairing reduces effective dissociation at high concentrations

If you have worked with concentrated hydrochloric acid in the lab, you will have noticed that the choking odor of hydrogen chloride gas is very apparent. How can this happen if this strong acid is really "100 percent dissociated" as all strong acids are said to be?

If you have worked with concentrated hydrochloric acid in the lab, you will have noticed that the choking odor of hydrogen chloride gas is very apparent. How can this happen if this strong acid is really "100 percent dissociated" as all strong acids are said to be?

At very high concentrations, too few H2O molecules are available to completely fill the extended hydration shells that normally help keep the ions apart, reducing the fraction of "free" H3O+ ions capable of acting independently. Under these conditions, the term "dissociation" begins to lose its meaning.

Although the concentration of HCl(aq) is never very high, its own activity coefficient can be as great as 2000, which means that its escaping tendency from the solution is extremely high, so that the presence of even a tiny amount is very noticeable.

Estimate the pH of a 10.0 M solution of hydrochloric acid in which the mean ionic activity coefficient - is 10.4.

Solution: pH = – log {H+} ≈ – log (10.4 × 10.0) = – log 104 = – 2.0

Compare this result with what you would get by using – log[H+]

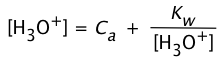

In this section, we will derive expressions that relate the pH of solution of a strong acid to its concentration in a solution of pure water. We will use hydrochloric acid as an example.

When HCl gas is dissolved in water, the resulting solution contains the ions H3O+, OH–, and Cl−, but except in very concentrated solutions, the concentration of HCl is negligible; for all practical purposes, molecules of “hydrochloric acid”, HCl, do not exist in dilute aqueous solutions.

In order to specify the concentrations of the three species present in an aqueous solution of HCl, we need three independent relations between them. These relations are obtained by observing that certain conditions must always be true in any solution of HCl. These are:

1. The autoprotolysis equilibrium of water must always be satisfied:

[H3O+][OH–] = Kw (4-1)

2. For any acid-base system, one can write a mass balance equation that relates the concentrations of the various dissociation products of the substance to its “nominal concentration”, which we designate here as Ca. For a solution of HCl, this equation would be

[HCl] + [Cl–] = Ca (4-2)

but since HCl is a strong acid and therefore no "HCl" exists in the solution, we can neglect the first term, so the mass balance equation becomes simply

[Cl–] = Ca (4-3)

3. In any ionic solution, the sum of the positive and negative electric charges must be zero; in other words, all solutions are electrically neutral. This is known as the electroneutrality principle.

[H3O+] = [OH–] + [Cl–] (4-4)

The next step is to combine these three equations into a single expression that relates the hydronium ion concentration to Ca. This is best done by starting with an equation that relates several quantities, such as Eq 4, and substituting the terms that we want to eliminate. Thus we can get rid of the [Cl−] term by substituting Eq 3 into Eq 4 :

[H3O+] = [OH–] + Ca (4-5)

The [OH–] term can be eliminated by use of Eq 3: (4-6)

(4-6)

This equation tells us that the hydronium ion concentration will be the same as the nominal concentration of a strong acid as long as the solution is not very dilute.

Notice that Eq 6 is a quadratic equation — but we don't want to go there yet!

Recalling that Kw = 10–14, it is apparent that the final term of the above equation will ordinarily be very small in comparison to the other terms, so it can be ordinarily be dropped, yielding the simple relation

![]() (4-7)

(4-7)

Only in extremely dilute solutions, around 10–6 M or below (where the plot curves), does this approximation become untenable. But even then, the effect is tiny. After all, the hydronium ion concentration in a solution

Only in extremely dilute solutions, around 10–6 M or below (where the plot curves), does this approximation become untenable. But even then, the effect is tiny. After all, the hydronium ion concentration in a solution

of a strong acid can never fall below 10–6 M; no amount of dilution can make the solution alkaline!

So for almost all practical purposes, Eq 7 is all you will ever need for a solution of a strong acid.

Make sure you thoroughly understand the following essential concepts that have been presented above.

- Estimate the pH of a solution of a strong acid or base, given its concentration.

- Explain the distinction between the concentration of a substance and its activity in a solution.

- Describe the origin and effects of ion-pairing in concentrated solutions of strong acids.

- Name and write formulas for the four major strong acids.